Eight Observations about Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – Part II

The Chancellor, having already raised taxation significantly, is set to implement another slug of tax increases this coming autumn

Part II – Observations 5) to 8)

I listened closely to Rachel Reeves’s Spring Statement on Wednesday 26th March and reviewed the technical documents released by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the official fiscal watchdog. I’ve also talked to numerous politicians, policymakers and investors – across Westminster, Whitehall and the City of London.

Since Wednesday, I’ve put together Eight Observations about the Chancellor’s actions. These are quite detailed and involve some close analysis, with lots of graphs and numbers. So rather than scare off all those who have subscribed to When The Facts Change since I launched on 19th March (2,500-plus and counting, thank you!), I’ve published this, my first major post, in two parts.

Observations 1) to 4) were released on Friday 28th March, detailing the following statements:

1) The UK’s public finances were weak when Labour took over, but then Reeves made them weaker still

2) This Spring Statement implies a LOT more borrowing …

3) … and that means higher debt interest payments

4) The state is getting bigger – and that poses serious financial dangers.

Here are Observations 5) – 8)

5) Growth is the answer, but Labour is hammering growth

Britain is teetering on the edge of fiscal credibility, with government spending running ahead of expectations, tax receipts lower than forecast and an increasingly large national debt that is in danger of sparking financial instability – resulting in much broader economic and societal damage.

The only way for the UK to genuinely and sustainably escape from our current fiscal bind is to grow the economy, so that debt falls as a share of GDP to less dangerous levels – and the rise in tax revenues and easing of welfare payments that growth automatically produces helps to cement a return to fiscal stability.

Yet, the £40 billion of extra taxation announced in the Chancellor’s October Budget statement has already significantly squeezed growth. And additional Labour policies are now set to undermine hiring, investment and enterprise even more. All that has compounded the UK’s fiscal weakness, with the country now at risk of enduring a serious bond market rebellion, sparking a more widespread financial crisis – as outlined in Observation 4) in Part I of this post.

Returning to growth requires, in my view, a lowering of the tax take from today’s 70-year high and the introduction of more commercially savvy regulation across a range of sectors. Yet following the October Budget, the UK’s tax burden – revenue as a share of GDP – is going up even more, from 35.3pc this year to a historic high of 37.7pc in 2027-28 according to OBR documents released alongside the Spring Statement, remaining at a high level until the end of this decade.

Returning to growth requires lowering the tax take from today’s 70-year high and more commercially savvy regulation across a range of sectors

Labour is also introducing a slew of growth-sapping regulation – not least Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner’s deeply counter-productive employment rights bill, currently going through Parliament. This extension of workers’ right – including the right to claim sick pay and unfair dismissal from day one of new employment contracts – will, on official estimates, add at least £5 billion to firms’ costs .

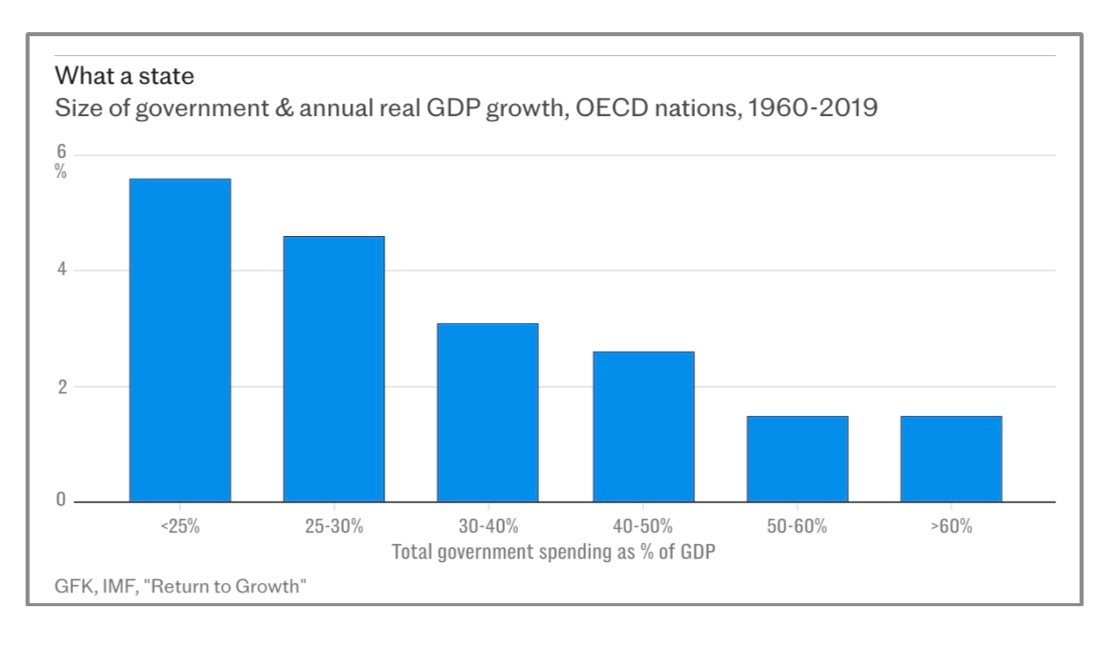

It is clearly the case that lower taxes in general foster GDP growth and a much higher trend level of consumption, investment and other economic activity. In his newly published book, Return to Growth, the businessman Jon Moynihan presents data from 28 countries across the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD).

As shown in Graph 1, from Moynihan’s book, growth numbers over the last sixty years demonstrate that economies with a tax burden of 25-30pc of GDP have expanded more than 4pc a year on average, while those with a burden of 40-50pc, where the UK is now heading, have grown merely half that amount. In general, the GDP of “small state” economies – where taxation and government spending are relatively low – has consistently increased much faster than that of economies where the tax burden is much higher. The historic evidence, across a range of countries over half a century and more, is unanswerable.

GRAPH 1: Size of state and real annual GDP growth, OECD nations, 1960-2029

Because low-tax economies grow faster, they generate the tax revenues needed to fund vital public services while still fostering economic activity and allowing enterprise to flourish, generating a low-tax-low-debt-high-growth virtuous circle. Yet Labour “pro-growth” agenda is taking place in the context of an already sky-high tax burden that’s about to go up even more – as detailed in Observation 1), in Part I of this post.

It’s worth noting that the fiscal impact of Rayner’s employment rights bill is yet to be assessed and included in the forecasts the OBR released on Wednesday. The precise scope of the legislation, which is yet to get through Parliament, remains unclear. But in a stark warning, the OBR signalled that the new rules will have a “material, and probably net negative, economic impact on employment, prices, and productivity”. In other words, the higher costs of doing business associated with Labour’s incoming extension of employment rights is likely to slow growth further, making the UK’s fiscal position even worse.

Because low-tax economies grow faster, they generate … a low-tax-low-debt-high-growth virtuous circle.

Rayner claims her incoming measures will “end exploitative zero-hour contracts”, resulting in a happier, more productive workforce – even though many casual part-time workers, not least students and parents juggling multiple jobs and childcare, benefit from the employment opportunities and flexibilities provided by zero-hour contracts.

The government’s determination to enforce sick leave and unfair dismissal entitlements from the very start of any period of employment has left businesses alarmed about significantly more red tape and exposure to the legal and reputational costs of countless vexatious claims. These measures will seriously curtail hiring, business investment and broader growth, as the OBR has warned, while undermining efforts to tackle Britain’s benefits crisis by getting millions of currently inactive people of working age back into work.

As well as acknowledging that Labour’s upgrade to workers’ rights will cost firms £5 billion a year to implement, official analysis also warns the new measures will have a disproportionate impact on small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – which will find it hardest to deal with the barrage of additional regulation. SMEs currently employ around two-thirds of the UK’s active workforce and are the engine-room of growth and innovation, accounting for at least half of total GDP.

Businesses large and small have been complaining loudly about the combination of incoming rises in employer NICs, the withdrawal of vital reliefs on business rates and the inflation-busting 6.7pc rise in the minimum wage from early April, also announced by Reeves in last October’s Budget. Labour’s new employment rights legislation comes on top of all that.

The Federation of Small Businesses is now warning that Rayner’s union-backed measures will “wreak havoc on our already fragile economy”, with a third of SMEs having already slashed hiring since Labour took office.

6) The OBR has “bailed-out” Reeves with risky future growth forecasts

Attention has focussed on the eye-catching headline halving of the OBR’s growth assumptions for 2025/26, from 2pc to 1pc. This slashing of forecast growth in the coming financial year was, of course, a blow to Rachel Reeves. And the economic slowdown in late 2024 and early 2025, and the prospect of a much slower expansion over the next twelve months is, of course, a major reason why the gilts market has become much more volatile of late, with yields trending upwards – given the knock-on fiscal implications of lower growth.

While wanting to appear that she is responding to these new realities, Reeves’s much-vaunted fiscal consolidation in the Spring Statement was a very long way from convincing. The main policy announcement was a package of savings on the current budget, amounting to £14 billion a year by 2029/30, partly in the form of cuts in departmental running costs (fewer civil servants) but also reductions in the welfare bill – making it harder for people to claim Personal Independence Payments (PIP). This has fuelled lurid accusations of a “return to austerity”, screamed by the left of the Labour party and promoted loudly by important parts of the UK’s broadcast media.

The reality is somewhat different. For a start, £14 billion is a drop in the ocean compared to public sector current spending forecast to still climb to £1,351 billion by 2029-30. That’s £219 billion more than in the current fiscal year – amounting to another significant increase in public expenditure, even allowing for inflation. So while media attention has focused on Labour’s £14 billion cut in annual public spending by 2029/30, less than 1pc, the reality is that overall state expenditure is rising by £219 billion – more than 19pc.

Some ministries, such as health, and now defence, are protected so will see large increases in their spending allocation, while some smaller departments will see actual reductions. The details will not be announced until the spending review finally reports in the summer. But while there will be endless complaints about “austerity”, the overall amount of government spending is, of course, still set to rise sharply during the rest of this Parliament.

While Labour is cutting annual spending £14 billion by 2029/30 – less than 1pc – overall state spending is still rising £219 billion – more than 19pc

Consider, for instance, the mooted welfare savings causing such tension between ministers and the Labour left. Some genuinely deserving cases will no doubt unfortunately lose their benefits as officials move to assess eligibility more rigorously, doing so rapidly given the politically charged nature of now “getting the welfare bill under control” after years of drift and neglect from all major parties.

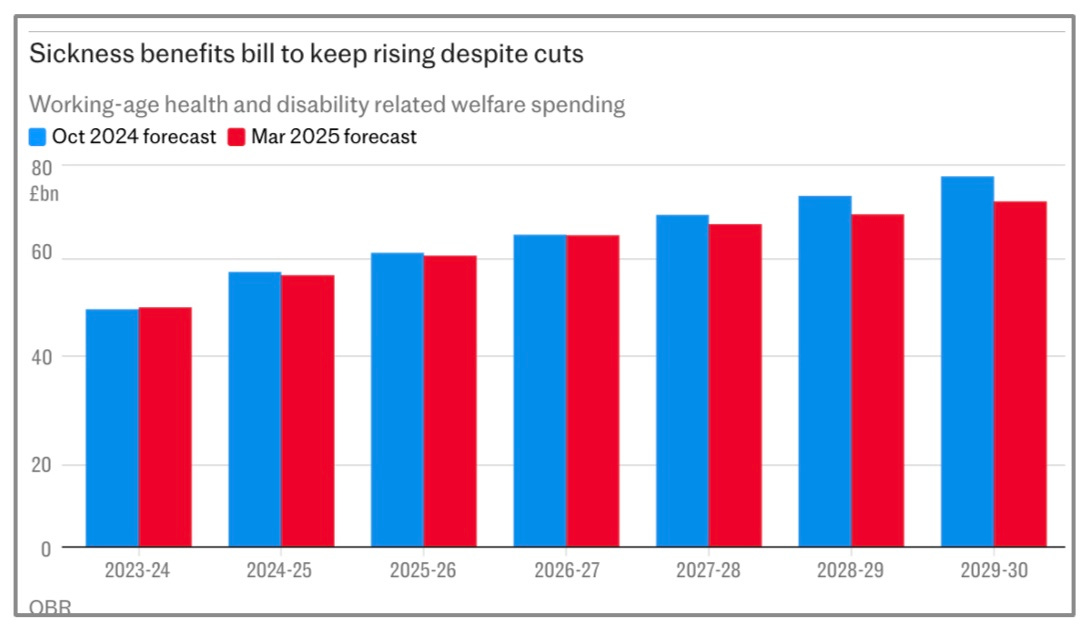

Yet the UK’s already huge sickness benefits bill will still rise sharply between now and the end of this decade, from less than £50 billion to well over £70 billion a year, as Graph 2 shows. So far from “cuts”, these welfare reforms amount to a minor slowdown in the rate of increase in a health-related benefits bill that will continue to surge upwards, fuelled by ever more government borrowing – leading to further increases in debt service costs, themselves financed by more borrowing still.

GRAPH 2: Sickness benefits bill, OBR updated forecasts

The £14 billion of annual savings may anyway not materialise. Consider the vaguely defined cuts in the costs of government departments. As of the end of last year, there were more than 548,000 civil servants on the public sector payroll – some 22pc more than the 446,000 employed in 2019, prior to lockdown, despite all the administrative advantages of modern technology including email, online conferencing and artificial intelligence. Despite that, the government’s “bold and decisive” plan to cut staff numbers by 10,000, a reduction of less than 2pc, will still be fiercely opposed by public sector unions with very close links to the Labour party.

The slowdown in the rate of growth of welfare spending may also turn out to be less than forecast, given the strength of feeling within the Labour movement, but also the signs of considerable behind-the-scenes bargaining between the Chancellor’s team and the OBR over the headline welfare savings number prior to the Spring Statement.

The OBR felt the need to say in the technical documents that the government’s welfare proposals “were sent to us very late in the process, and late notice of changes and incomplete analysis hampered our ability to reflect these measures in our forecasts”. It’s clear that not all the increase in defence spending announced by Reeves were including in the OBR’s calculations – with the ramifications of the new workplace rights legislation also left out, as discussed above.

On Wednesday, Reeves made a great deal of the fact that she has managed to “restore in full our fiscal headroom” by 2029/30. What this means is that the OBR judges, in its central scenario, that by the end of the forecast period, the government will meet its fiscal rules with a financial buffer of £9.9 billion, the same safety margin as at the time of last October’s Budget. This is examined in more detail in Observation 8) below.

But in securing this “headroom”, Reeves is relying heavy on GDP growth assumptions over the coming years which drive the fiscal outcomes modelled by the OBR relating to taxation, spending, borrowing and everything else. These growth forecasts are, in turn, heavily dependent on the government’s “planning reform” proposals designed to boost construction – that, is housebuilding schemes and other major infrastructure projects enabled by new limitations on the scope for objections by so-called Nimbys.

The reality is, though, that even if planning permission is granted for new residential and infrastructure building projects, actual construction could easily be hobbled by skills shortages or a lack of access to working capital, particularly if the economic backdrop continues to be fragile.

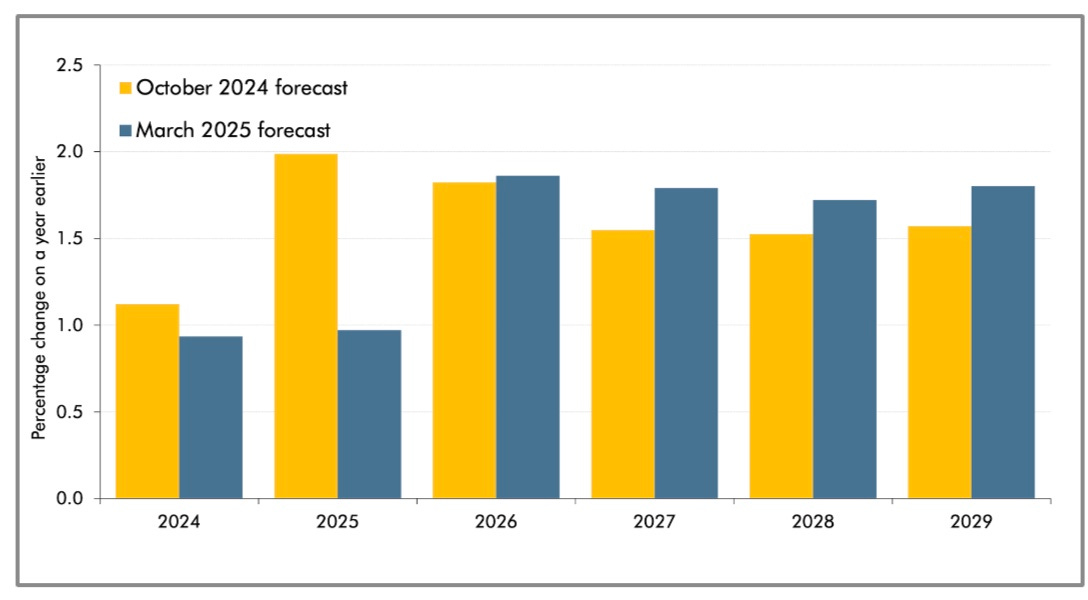

It was no surprise that the OBR sliced the 2025/26 growth forecast in half, from 2pc to 1pc. This was widely expected, given that the Bank of England cut its growth estimate for the coming financial year from 1.5pc to 0.75pc back in February – and countless international bodies such as the International Monetary Fund and the OECD have similarly downgraded UK growth forecasted for 2025/26.

Even if planning permission is granted for building projects, actual construction could be hobbled by skills shortages

But it seems clear to me, looking at Graph 3, that the only reason the Chancellor’s plans look remotely credibly over the next five years is because the OBR, while taking the unavoidable decision to slash its immediate 2025/26 growth forecast, has on the other hand jacked up its predictions, significantly in most cases, for each of the subsequent years of this Parliament – namely 2026/27 to 2029/30 – for pretty unconvincing reasons.

GRAPH 3: Real GDP growth outcomes and OBR forecasts

Reeves used the word “uncertain” no less than seven times on Wednesday, referring again and again to “uncertain global markets”. The Chancellor also repeatedly pointed out that “the world has changed” – journalists covering her speech were literally playing “Spring Statement buzz-word bingo”. Government spin-doctors backed up her efforts, claiming that “a changing world” has been the reason for the striking growth undershoot and cut in the OBR’s immediate forecast since last October, rather than Labour’s counter-productive rises in taxation, borrowing and regulation.

But if such changes – in the form of US tariffs and other barely specified escalations of geopolitical tension – are to have such a negative impact on growth in 2025/26, why are the UK’s GDP growth forecasts for three of the subsequent four years each a chunky 0.2 percentage points higher?

Having spoken to quite a few people in the OBR and around the top of the Labour party, the only reasons they offer for this significant rise in forecasted growth during the second half of this Parliament are dubious planning reforms and spurious gains in productivity.

The growth boost from planning reform is, as mentioned, highly dependent on addressing the chronic skills shortages across the UK construction sector, after years of misguided over-emphasise on broadening university education and failed attempts to revitalise apprenticeship schemes. Perhaps this is why Reeves was photographed holding a brick-laying trowel at a vocational college five days before her Spring Statement.

The Chancellor used that visit to announce £600 million of funding to train 60,000 more skilled construction workers over the next four years – so £150 million per year. The government is pledging 1.5 million homes will be built over the same time-period – so that’s one extra skilled worker for every 25 news homes, hardly a striking increase. And that assumes all 60,000 workers are immediately trained and materialise quickly on building sites across the country.

The only reason growth forecasts have been significantly raised during the second half of this Parliament is dubious planning reforms and spurious gains in productivity

“One in eight young people are not in employment, education or training,” observed Reeves during her Spring Statement. “If we do nothing, we are writing off an entire generation”. There were indeed 987,000 “Neets” – not in employment, education or training – aged 16-to-24 in the UK at the end of 2024, up no less 13pc from the previous year. Such young people are precisely those most likely to benefit from the chance to learn carpentry, plumbing or other construction trades.

Yet for all her own bricklaying skills, Reeves’s decision to hike the minimum wage for 18-20-year-olds and apprentices by an inflation-busting 16pc and 17pc respectively, announced in her October Budget but to be implemented from early April, is hardly likely to help persuade firms to provide much-needed on-the-job training, in construction or anything else, for such youngsters.

7) “Productivity isn’t everything, but it is almost everything”

That then leaves the growth of productivity – that is, output per worker – as the final source of a significant uptick in GDP growth, short of the decisive cut in taxation, regulation and other supply-side constraints on employment, investment and enterprise that this Labour government appears to be intellectually, ideologically and temperamentally incapable of delivering.

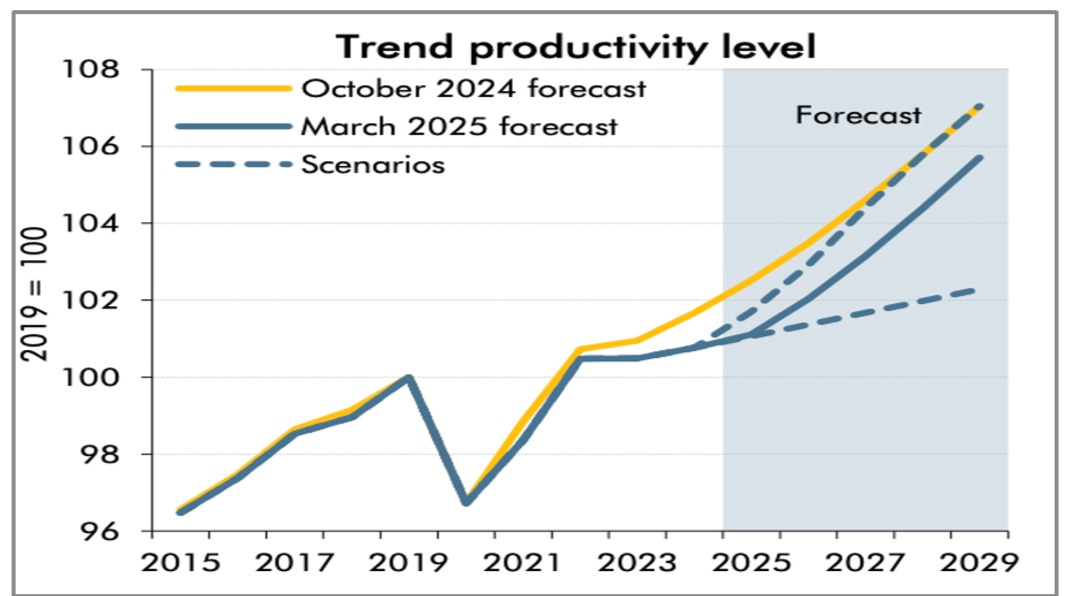

The OBR forecasted a significant increase in the UK’s trend productivity level back in 2023 and again in 2024. In both cases, measured productivity remained stubbornly flat. So now the official fiscal watchdog has now once again simply shifted the same projected productivity rise forward another year – as shown in Graph 4 below.

GRAPH 4: Trend Productivity Level, OBR forecasts

The British state employs just over 20pc of the workforce. And public sector productivity remains well below its pre-Covid levels – with output per state worker having plunged over recent years. That’s hardly surprising, given the explosion of “working from home” and the fact that we now have over a fifth more civil servants than just prior to the pandemic, as outlined above.

It is almost impossible to envisage a recovery in public sector productivity without widespread and fundamental reforms. Yet Reeves is proposing only a 2pc cut in headcount, as mentioned before – and that could well prove tough to implement, given that it will likely be resisted by recalcitrant staff and trade unions at every stage.

But will output per worker rise like Lazarus across the economy as a whole, driving the GDP growth upticks that will ensure Reeves’s sums add up by the end of this Parliament? Almost certainly not. Even the OBR itself “points to the downside risk around its all-important productivity assumptions”.

The official watchdog wrote that “significant uncertainty surrounds domestic and global economic developments” – which impacts the path of future productivity, of course, dependent as it is in factors relating to the labour market, the availability of capital, energy prices and much more besides.

The OBR’s technical documents released alongside the Spring Statement are, in fact, full of warnings that the productivity growth surge at the heart of pretty much all the calculations and forecasts pertaining to the UK’s public finances over the next five years may not happen. “One of the single greatest risks to the fiscal outlook arises out of the difficulty in interpreting what the most recent combination of population, employment, and GDP data implies for the future productivity of the UK economy,” says the OBR.

“One of the single greatest risks to the fiscal outlook arises out of the difficulty in interpreting … the future productivity of the UK economy,” says the OBR.

The latest data from the Office for National Statistics shows that labour productivity, instead of rising, actually fell by around 1pc over the course of last year. And, the OBR continues, “if the projected recovery in UK productivity growth fails to materialise, and it continues to track its recent trend, then output would be 3.2pc and the current budget would be 1.4pc of GDP in deficit by the end of this decade”.

That, the OBR has confirmed, would see Reeves miss her fiscal target by a staggering £48 billion in 2029/30 – a shortfall almost five times greater than her much-vaunted £9.9 billion of “fiscal headroom”.

“Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it’s almost everything.” This, in my view, is one of the greatest aphorisms ever coined in the history of economics. I don’t always agree with Paul Krugman, the US economist Nobel Laureate. But when he wrote that phrase back in the early 1990s, he combined writing talent with deep economic insight.

8) There is no genuine “headroom”, so Reeves will hike taxes even more

“As a result of the steps that I am taking today, I can confirm I have restored in full our headroom against the stability rule”, Rachel Reeves told the House of Commons on Wednesday, with a flourish. This means that, according to the OBR, the Chancellor has set spending, taxation and borrowing on a path that meets the government’s fiscal mandate for the current budget to be in balance in 2029-30, with a buffer – known as “fiscal headroom” – of £9.9 billion, as mentioned above.

Less than five months on from her inaugural Budget in October, the Chancellor has essentially been forced to make fiscal adjustments due to the slowdown in GDP growth sparked by her sharp tax rises and rising debt service costs – as gilt traders, taking an increasing dim view of the UK’s government finances since last October in the context of slowing growth, have pushed yields to a sixteen-year high.

Just ahead of the Spring Statement, the OBR estimated that the government was on course to miss this “stability rule” by £4.1 billion. The £14 billion of annual savings Reeves is now claiming by 2029/30 following Wednesday’s measures takes the safety margin to £9.9 billion – the same as the headroom she declared back in October.

But £9.9 billion of headroom on total spending of £1,351 billion in four years’ time is a contingency of well below 1pc – so small as to be meaningless. The OBR, after no doubt extended negotiations with ministers and Treasury officials, describes this buffer in a devastatingly matter-of-fact way as: “a very small margin compared to the risks and uncertainty inherent in any fiscal forecast”.

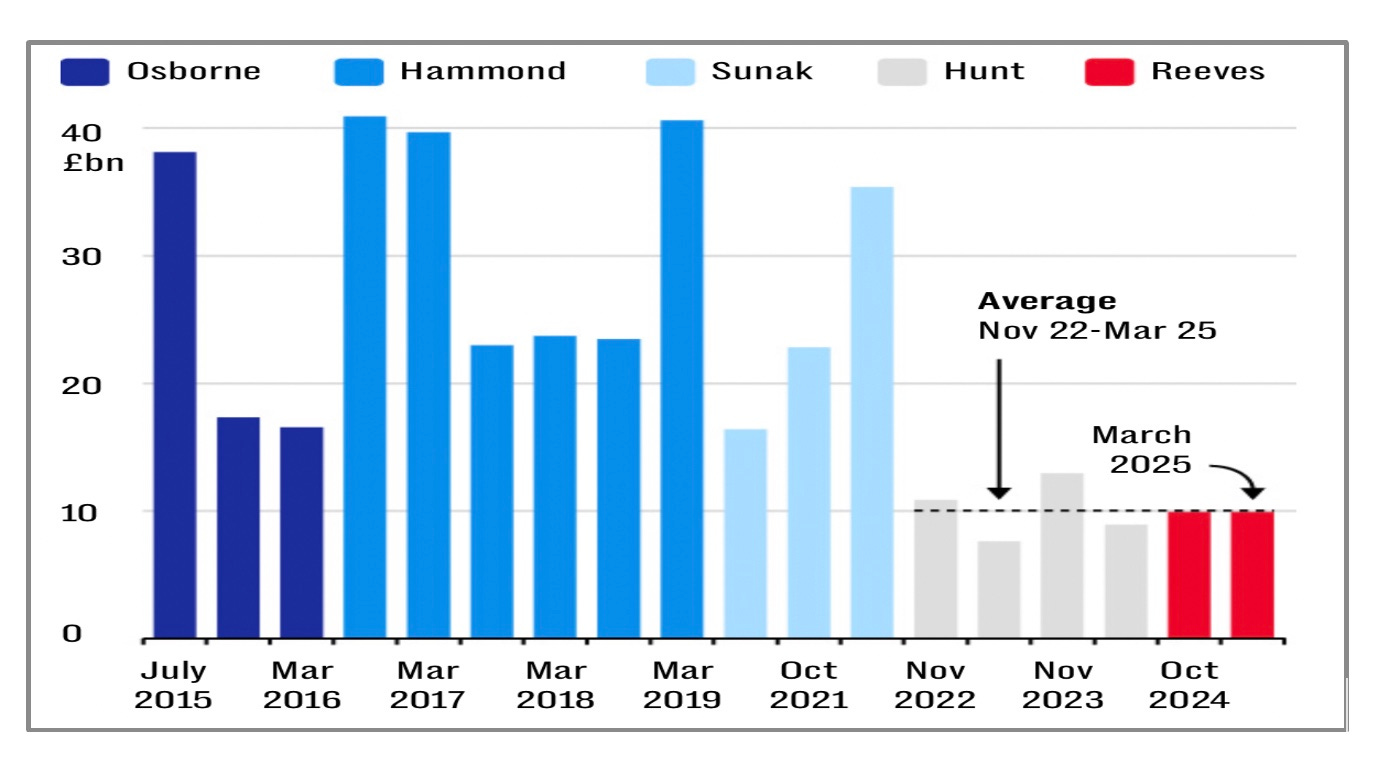

The “headroom” left by Reeves is, the OBR reminds us, only one-third of the £31.3 billion average margin that Chancellors have set against their fiscal rules since 2010 – as illustrated in Graph 5. This, at a time of when global uncertain is rising, as Reeves herself was so keen to point out last Wednesday.

GRAPH 5: Successive forecasts for “headroom” against fiscal targets

Prior to the Covid pandemic, Chancellors would routinely allow fiscal headroom of £20-£40 billion. But since lockdown, the UK’s public finances have been so weak that headroom has shrunk significantly, as Treasury ministers have taken ever more risks with the public finances – which is one reason why market borrowing costs demanded of government have gone up, even as the Bank of England has lowered benchmark interest rates over recent months.

The OBR describes Reeves’s £9.9 billion of headroom as a “very small margin compared to the risks and uncertainty inherent in any fiscal forecast”

This miniscule margin for error Reeves has left in the UK’s public finances could easily be wiped out by new shocks, not least a further rise in gilt yields or even a relatively minor global trade war. The Chancellor has allowed no extra headroom at all since her Budget back in October – and the OBR now points to “significant risk” around even its main “central” forecast.

“Since early October, daily ten-year gilt yields have varied by a full percentage point between 3.9pc and 4.9pc,” the OBR reminds us. “It would only take a 0.6 percentage point increase in market expectations for gilt yields ... to tip the current balance from a £10 billion surplus back into deficit in 2029-30, the target year for the Chancellor’s fiscal rules”, the OBR then observes.

In other words, all it would take would be for market interest rates to rise 0.6 percentage points higher, less than the 1 percentage point volatility we’ve seen in ten-year yields over the last five months, to eliminate the entire impact of Reeves’s savings on welfare spending and other costs, wiping out her “headroom” entirely. We are talking, then, about a rise in the ten-year gilt yield from around 4.7pc just before the Spring Statement to 5.3pc.

A relatively minor increase in collective nervousness across financial markets, then, a small further deterioration in market sentiment towards the UK’s fiscal position – far from impossible as the government becomes embroiled in political rows regarding welfare savings or trade policy over the coming months – and the Chancellor’s efforts to reset Britain’s budgetary plans and rebuild credibility in her Spring Statement would have come to nought, with Reeves then under enormous pressure to make yet more painful fiscal adjustments.

This gilt yield risk is in addition, of course, to the “significant uncertainty” regarding the growth of UK productivity – outlined in the previous section. To remind readers, if output per worker doesn’t improve from its current trajectory, the OBR has forecast, Reeves will miss her fiscal target by £48 billion in 2029/30 – a shortfall almost five times greater than the “headroom” she has allowed.

Then there is inflation risk on top of that. Whether or not those all-important gilt yields continue on the upward trend of recent months depends in turn, on inflation – with high inflation driving investors to charge the government even more to borrow. Prior to the Spring Statement, we learnt the consumer price index (CPI) increased by 2.8pc during the year to February, down from 3pc the month before. While this was good news, it’s a temporary reprieve, with inflation set to rise significantly over the coming months.

Already, other inflation measures are outstripping the CPI, with service sector inflation running at 5pc in February. The OBR is now forecasting that the recently announced rise in the Ofgem price cap, which will push up energy bills, coupled with higher water bills and also food prices will see CPI inflation hit 3.8pc this coming July – see Graph 6. That’s almost twice the Bank of England’s 2pc target.

GRAPH 6: UK Consumer Price Index, annual increase

Other inflationary pressures include Reeves’s tax rises themselves plus Labour’s union-driven extension of workers’ right, both of which will push up firms’ costs significantly. Then there’s the danger of geopolitical squalls, not least US tariffs and potential oil and gas price spasms, hiking inflation even more.

Whether or not those all-important gilt yields continue on the upward trend of recent months depends in turn, on inflation

The OBR documents disclose that, overall, “the probability of meeting the fiscal mandate is 54pc”. Given the confluence of risk under a wide variety of headings – from debt-service costs to productivity and inflation – to say nothing of the political objections within the Labour movement, from top to bottom, of actually implementing fiscal consolidation – I would say 54pc is a very rosy estimate, and the true probability of this fiscal target sticking is a percentage well within single digits.

Overall, this Spring Statement was an attempt by Reeves to delay much tougher decisions ahead of her Spending Review in June – where she will be forced to reveal her specific choices in terms of expenditure allocation to each government department. This is a process likely to win her few allies within the Labour party.

Beyond that Spending Review, even small downgrades to the OBR’s forecasts could mean more action is needed to fill a fiscal hole. Given global risks and the potential for financial market volatility, significant additional growth downgrades are entirely possible.

The Chancellor is now in a position where she is sticking to “iron-clad” fiscal rules but with no headroom – which leaves her, her party, the government, and the UK’s entire fiscal policy at the mercy of events. Even the extremely modest cuts Reeves announced ahead of the Spring Statement are causing a serious backlash among Labour MPs, making further cuts less likely.

The Chancellor might try to alter her fiscal rules. But I’d say this is unlikely – as it would be very badly received by the gilts market, making a bad situation worse. Faced with another “hole” in the public finances, Reeves’s instinct will overwhelmingly be to plug the gap mainly with taxation and additional borrowing, rather than lower spending or an attempted rule change.

We are about to embark, then, on months and months of speculation about which taxes she may or may not increase in her Autumn Budget. That uncertainty will loom extremely heavily over an economy which, after multiple tax rises to be introduced in early April, will already feel very heavily burdened.

We are about to embark on months and months of speculation about which taxes Reeves may or may not increase in her Autumn Budget.

Amidst the welter of rhetoric and statistics, Reeves referred to “the party opposite” no less than ten times during her Spring Statement – seeking to deflect blame for the UK’s stagnating economy, preparing the ground for another manifesto-breaking tax rise. The trouble is that raising taxes further will slow down the economy to an even greater extent, making the public finances even weaker.

But Reeves doesn’t want to admit that – not least as much of the Labour movement has an ideological preference for higher taxes. So I fully expect her to raise taxes further later this year – even if she does so using “stealth” measures such as freezing income tax thresholds for even longer and/or putting yet more levies on businesses that many MPs and journalists will struggle to understand.

Overall, this Spring Statement amounts to irresponsible tinkering at the edges of fiscal policy when a fundamental reshaping is required in numerous areas. We are indeed living in a “changing world”, as Rachel Reeves said on Wednesday, and the imposition of tariffs by the new US administration would have a wide-ranging impact. While that provides an even more compelling reason to commit to a comprehensive trade deal with the US, undertaking the required domestic regulatory reform, Reeves will likely be ideologically opposed, so missing a potentially historic opportunity.

The Chancellor often asserts that “delivering growth is this government’s number one priority”. Doing so would certainly be the best way, the only way in fact, to put the UK’s public finances back on an even keel. But the reality is that Labour’s employment rights bill, by curtailing hiring and increasing red tape for firms, is likely to kill growth. The ongoing dogmatic implementation of the 2008 Climate Change Act, which means UK firms and households are living with the highest energy prices in the world, four times above those in America, is killing growth. Policies driving wealth creators (and their investment and tax revenues) out of the country are also killing growth.

In a few days’ time, the UK will endure a sharp rise in employer national insurance contributions, along with a number of other corporate tax increases. On top of that, council taxes are going up by twice the rate of inflation – as the overall tax burden increases even more from its current 70-year high.

The overall state of the British economy and the public finances remains very delicately and dangerously balanced. Twenty years ago, the private sector represented two thirds of the UK’s GDP, but today it is just over half. As Keith Joseph remarked in his 1976 Stockton Lecture, the “rider is now heavier than the horse”.

To foster desperately needed growth, Labour needs to get out of the way, allowing the confidence of the private sector to be rebuilt, rather than taxing and regulating the economy into further stagnation. Public spending needs to be constrained, allowing tax cuts that will get growth going, raising more actual revenues in turn.

And with public sector net debt as a share of GDP at its highest level in more than fifty years, borrowing also needs to be brought back under control. It has now reached levels where any further significant rise in gilt yields threatens fundamentally to destabilise the government’s finances, sparking a 1976-style systemic crisis.

I very much doubt, unfortunately, that Labour has the intellectual grit or determination to take the correct path back towards fiscal stability. By far the most likely outcome is that Reeves, if she survives as Chancellor, imposes more fiscal consolidation in her Autumn Budget in the form of further tax rises – which will be deeply counter-productive.

And while she has so far ignored the siren calls from left-wing commentators and social media celebrities for additional taxes on wealth, which would backfire by deterring investment and driving more taxpayers overseas, I suspect she will ultimately succumb, in a bid to shore up her own personal support within the Labour movement.

Fantastic duo of articles, who says macro economics is boring?

My analysis of the situation is pretty simple. If we understand growth is a byproduct of a thriving private sector then by definition doing anything that gets in the way of companies making profits and growing is anti-growth. Employment rights, regulation and taxation are drags on companies performance. If the government was serious about growth they’d do everything in their power to help business make more money, but that idea runs philosophically counter to labours world view.

Speaking as a man who failed A-Level economics, thank you Liam for putting in this in terms I can grasp! A request, if I may? Could you (here or with Allison) do a piece on tariffs, which are very much a subject du jour, about which I am similarly confused.