Eight Observations about Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement - Part I

The Chancellor is taking huge risks with the UK’s financial stability

PART I: Observations 1) to 4)

I listened closely to Rachel Reeves’s Spring Statement on Wednesday 26th March and reviewed the technical documents released by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the official fiscal watchdog. I’ve also talked to numerous ministers, policymakers and investors about the Chancellor’s speech and the UK’s fiscal and economic outlook – across Westminster, Whitehall and the City of London.

Since Wednesday, I’ve put together eight observations about the Chancellor’s actions. These are quite detailed and involve some close analysis, with lots of graphs and numbers. So rather than scare off new subscribers to When the Facts Change (2,000-plus since I launched just over a week ago and counting, thank you!), I’ve decided to publish this, my first major post, in two parts.

Observations 1) to 4) are below. The second half of this post – Part II: Observations 4) – 8) – will be posted tomorrow (Saturday 29th March)

Please feel free to share and comment.

1) The UK’s public finances were weak when Labour took over, but then Reeves made them weaker still

Britain is teetering on the edge of fiscal credibility, with government spending running ahead of expectations, tax receipts lower than forecast and an increasingly large national debt that is in danger of sparking financial instability – resulting in much broader economic and societal damage.

Back in October, in Labour’s first Budget Statement for 14 years, Chancellor Rachel Reeves upped government spending by £70 billion per annum on average during this Parliament, financed by £30 billion of extra state borrowing each year and £40 billion of additional annual taxation. That’s equivalent to a 5pc rise in the UK’s combined tax bill – most of it falling on businesses, but with serious knock-on effects for workers and households too.

The sizeable tax rises announced last autumn don’t take effect until early April – the start of the new financial year 2025/26. But just the prospect of the £25 billion rise in employer national insurance contributions has, over recent months, been enough to hammer both business and consumer confidence, with hiring and investment by firms down sharply since last autumn, causing economic growth to stall.

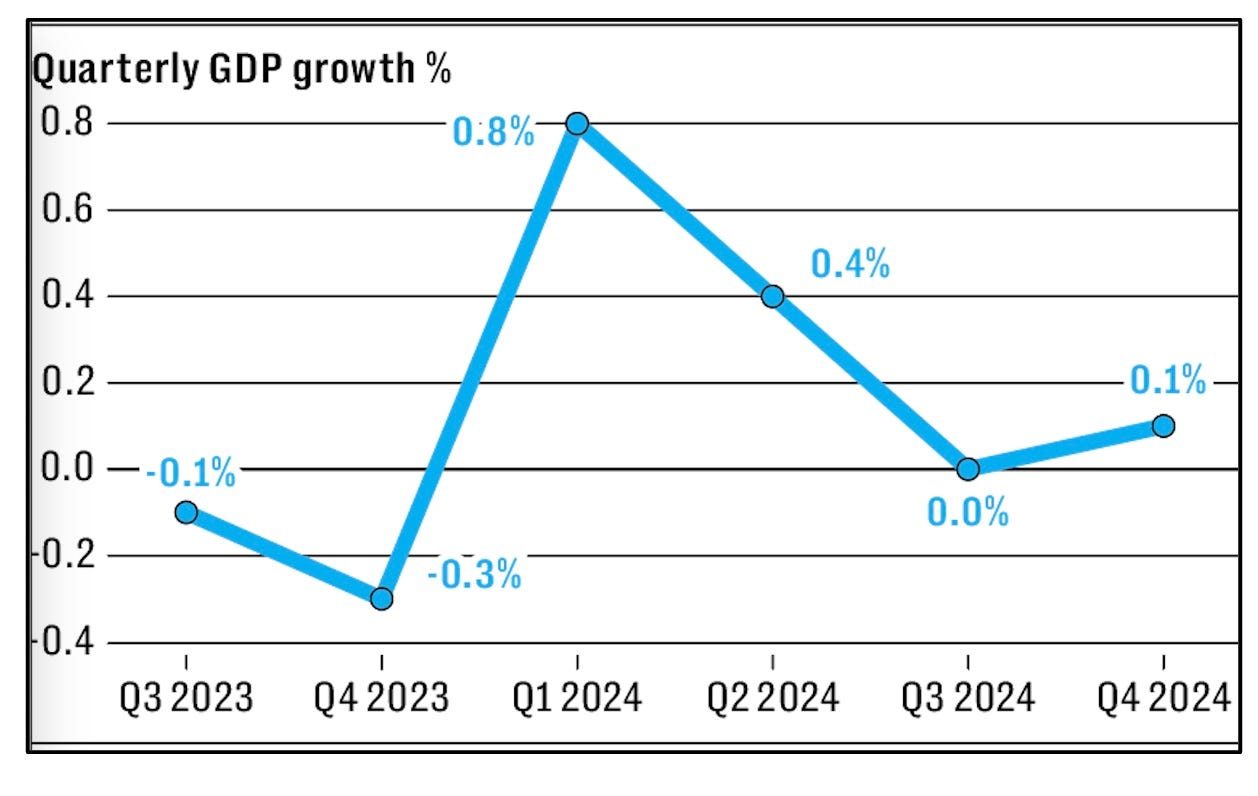

Under the Tories, the economy was relatively buoyant during the first three months of 2024, as Graph 1 shows, expanding by 0.8pc compared to the previous quarter and still managing a decent 0.4pc growth rate during the three months to June.

GRAPH 1: UK GDP Growth, quarter-on-quarter

Over the second half of last year though, following Labour’s July election victory, and particularly following Reeves’s October tax-raising Budget, the economy flatlined. And on the latest figures, the UK economy has begun to shrink, with GDP contracting 0.1pc during January, instead of growing 0.1pc as expected.

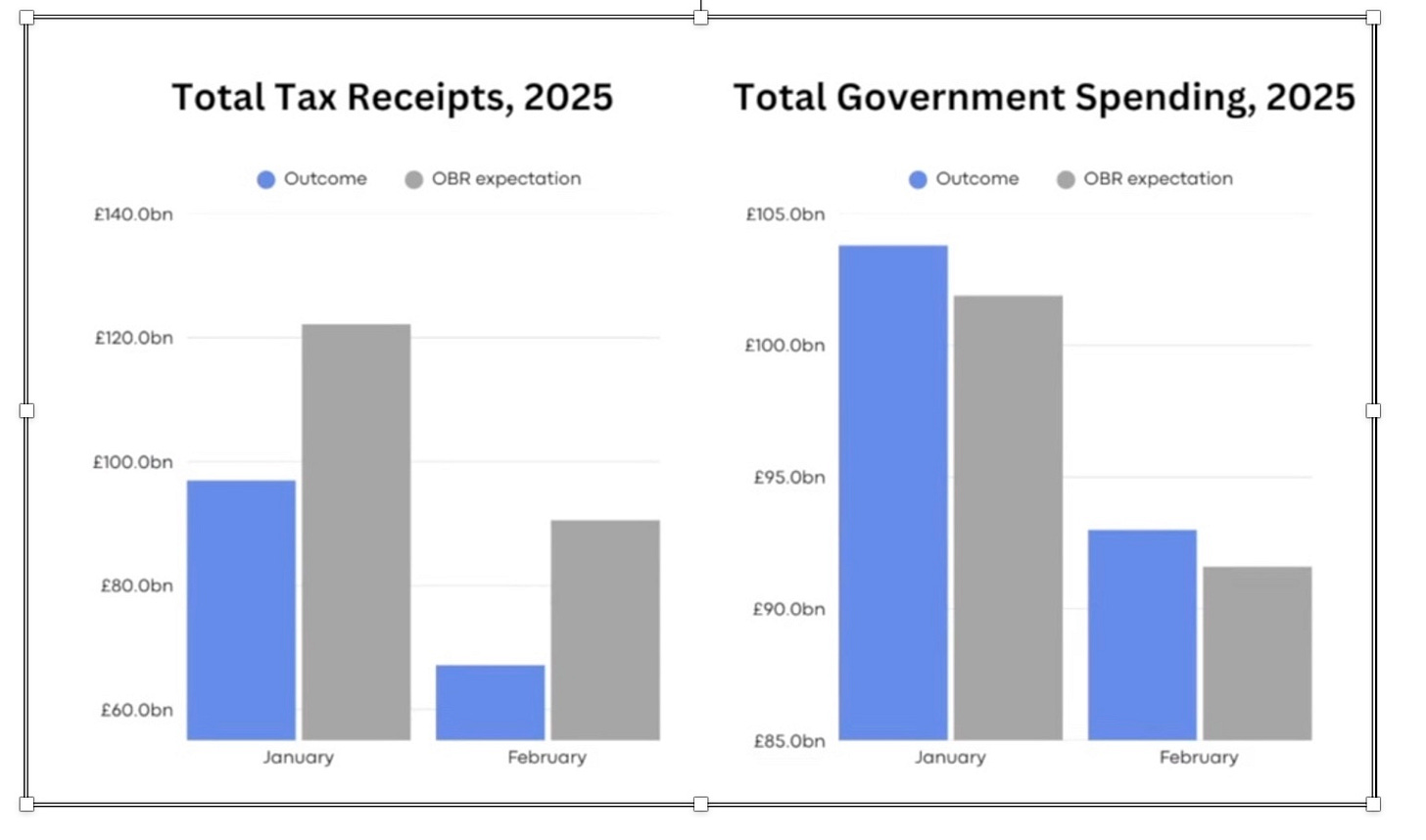

When growth is much slower than forecast, and especially when economic activity is curtailed and GDP falls, then tax revenues turn out much lower than predicted, with spending on benefits and other support measures much higher, pulling the public finances apart in both directions.

That’s illustrated in Graph 2 below, showing tax receipts much lower and government spending significantly higher during January and February than predicted by the official fiscal watchdog the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) at the time of Reeves’s Budget back in October.

GRAPH 2: Fiscal outcomes compared to OBR October 2024 forecasts

It can’t be said enough that after winning last July’s general election, Labour inherited a pretty tough fiscal situation from the Conservatives. The UK tax burden – revenues as a share of national income – was already at a 70-year high and the national debt was pushing 100pc of annual GDP. That compares to a national debt of less than 40pc of GDP when Labour took office under Tony Blair back in 1997.

When growth is much slower than forecast … then tax revenues turn out much lower than predicted, with spending much higher, pulling the public finances apart in both directions.

Having said that, Reeves made a bad situation much worse last October, taking large risks by ramping up public spending – and therefore borrowing and taxation – at a time when the public finances were already extremely fragile and the economy was struggling to finally escape the lingering impacts of the UK’s unduly stringent Covid-related lockdown.

That’s why this latest Spring Statement was, to all intents and purposes, an “Emergency Budget” in all but name. The government line is that “the world has changed”, a phrase ministers have been using ad nauseum in recent days – with the Chancellor blaming Trump’s trade policies while stressing the “now pressing need” to prioritise defence spending.

But for Reeves to be forced to come back to Parliament to change her spending plans within six months of what she herself called a “once in a parliament Budget” last October – and to do so in the middle of a spending review – is, to say the least, highly unusual.

2) This Spring Statement implies a LOT more borrowing …

The Chancellor’s main aim with this Spring Statement was to try to reassure increasingly skittish financial markets that she has a firm grip of the public finances. “We have seen what happens when a British government borrows too much”, Reeves told the House of Commons – a sideswipe at the short Premiership of Liz Truss, during which gilt yields spiked upward, causing the former Prime Minister to be drummed out of office.

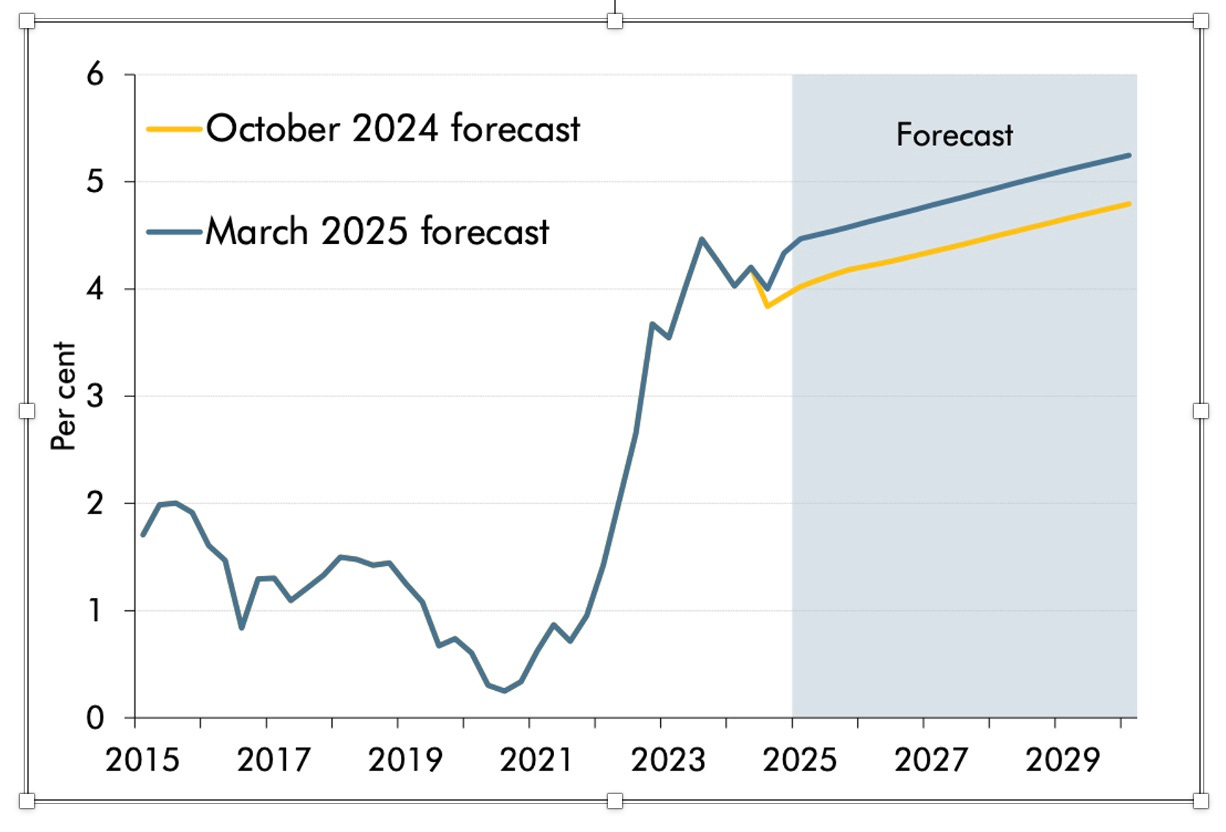

The reality is, though, that the UK’s 10-year yield – what the government is charge by financial markets to borrow for a decade – has risen by around 0.75 percentage points since last summer and has, in recent months, been consistently above 4.5pc. That’s significantly higher than the peak reached at the height of the “mini-budget crisis” under Truss’s leadership back in 2022, as shown in Graph 3.

GRAPH 3: 10-year gilts yields (UK government borrowing costs)

Since October, global pension funds, insurance companies and other large institutional investors which invest in sovereign bonds, lending governments money, have been taking an increasingly dim view of the UK’s public finances – and, as a result, have been charging the government more to borrow. Two days ahead of the Spring Statement, on 24th March, the 10-year yield was well above 4.7pc, with government borrowing costs at their highest level since the 2008 financial crisis – and on a decidedly upward trajectory.

All this explains why Reeves was under such pressure to consolidate the UK’s public finances – in a bid to convince investors that this Labour government is willing to take on spendthrift left-wing MPs and trade union paymasters and that senior ministers do actually understand the economic facts of life. And that involves imposing some painful spending constraints.

That’s why during the month ahead of the Spring Statement, Work and Pensions Secretary Liz was ordered to scramble together reforms designed to achieve £4.8 billion of annual net savings in the welfare budget

It's also why, in a Spring Statement lasting barely half an hour, Reeves used the word “secure” six times – echoing her pre-election pledge to pursue “securonomics”, whatever that is – and “stability” got no fewer than ten mentions, not least in the Chancellor’s repeated refrain to “secure our financial stability”.

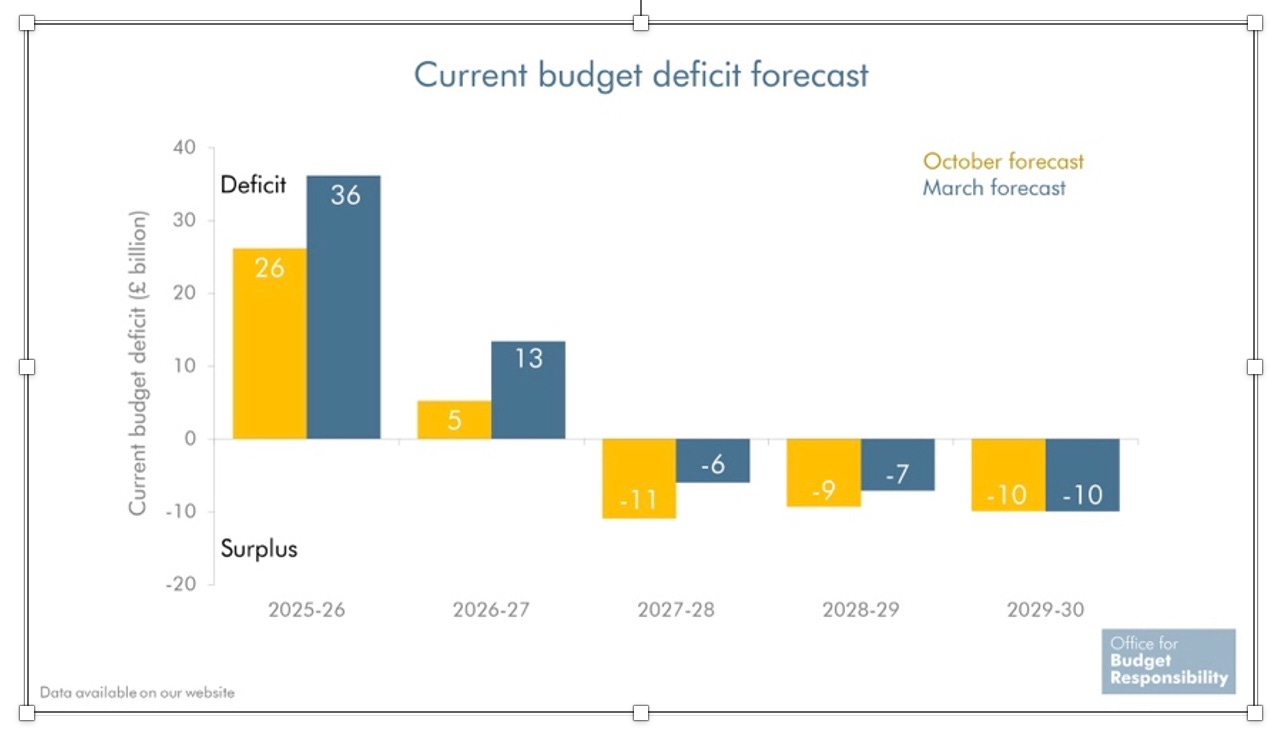

Despite this rhetoric, the reality is that far from reining in state largesse, Reeves revealed on Wednesday that the government is actually on course to borrow a lot more than previously forecast by the OBR back in October – as shown in Graph 4.

GRAPH 4: OBR updated UK budget deficit forecasts

The forecast fiscal deficits for 2025/26 and 2026/27 have both increased significantly, by £10 billion and £8 billion respectively. That suggests extra borrowing of £18 billion over the next two years.

Since October, global pension funds and other large institutional investors that invest in sovereign bonds, have been taking an increasingly dim view of the UK’s public finances

How much is £18 billion? Well, it’s almost twice the savings the Chancellor says Labour will secure over two years by, in her words, “fundamentally reforming the welfare state” – with all the political fire and brimstone that will involve.

So far from acting to “secure our financial stability” in this Spring Statement, Reeves is actually doubling down again, as she did in October, taking yet more huge risks with the UK’s public finances by significantly increasing government borrowing.

3) … And that means higher debt interest payments

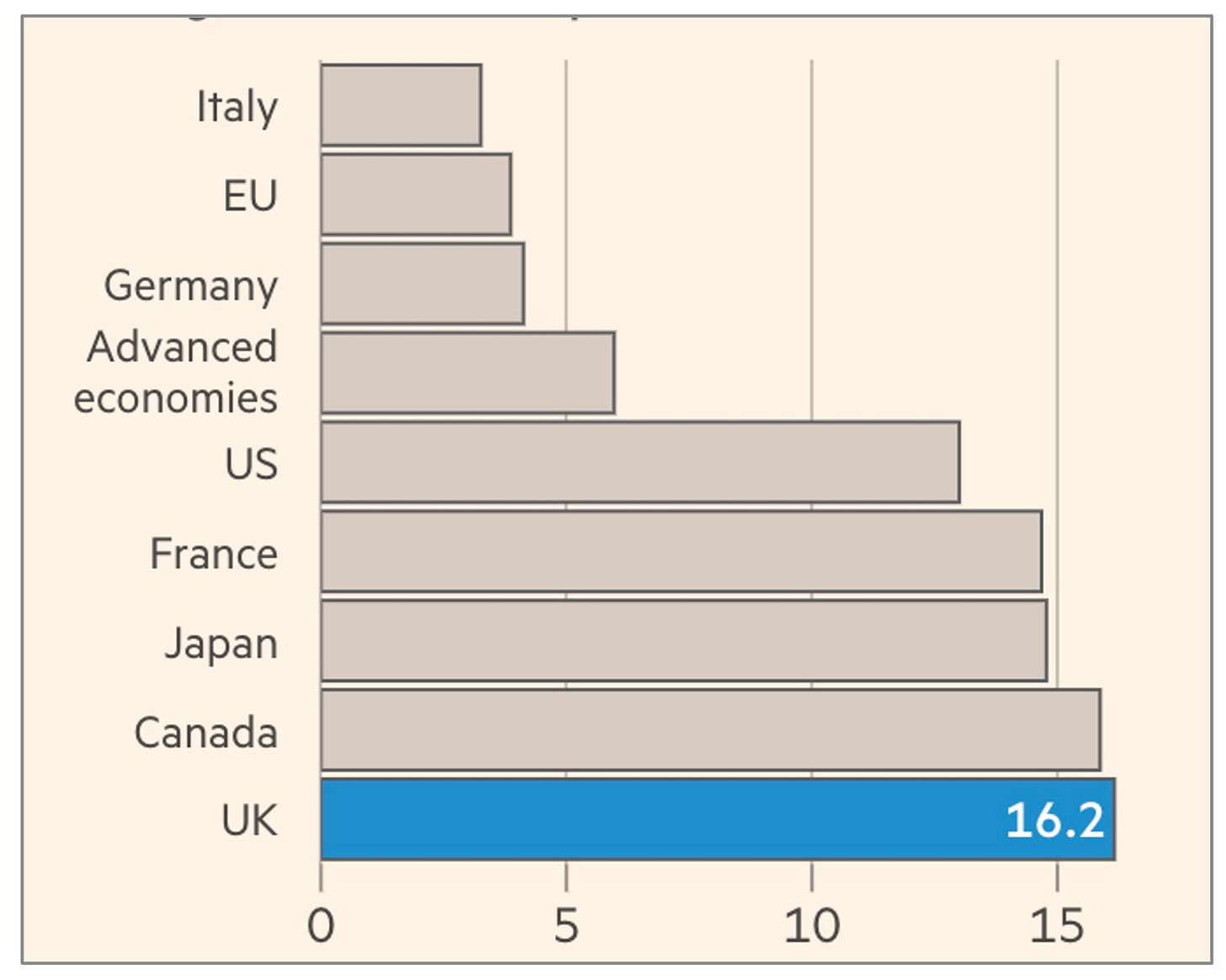

UK government debt as a share of GDP remains “mid-table” among the G7 economies – with gross debt of 101pc of GDP in 2024, compared to 123pc in the US, 112pc in France, 139pc in Italy and 60pc in Germany. But since the start of lockdown, Britain’s public debt burden has surged faster than that of any other large “advanced economy”, not least due to the massive sums spent on the furlough scheme, and the ever-widening gap between public spending and the tax revenues generated by a relatively sluggish economy.

Britain’s gross government debt as a share of GDP has increased by more than 16 percentage points since 2019 (lockdown began in March 2020), as shown in Graph 5, compared to an average increase of less than 5 percentage points across the European Union as a whole.

GRAPH 5: Change in gross state debt since 2019, GDP percentage points

It’s the fast build-up of sovereign debt, rather than long-standing debt levels, that really spooks financial markets – and the sense that an accelerating debt increase isn’t being taken seriously enough by policymakers so may not be curtailed. When countries continuously live beyond their means, the danger is that they end up borrowing ever more to pay the debt interest on existing borrowing, risking a disastrous collapse into insolvency. The prospect, at least, of that risk has lately been emerging in the UK.

Since lockdown, Britain has been consistently borrowing £10-15 billion a month – an enormous amount. Consider that raising income tax by a penny, a hugely controversial move, would raise around £7 billion across an entire financial year.

Consider also that in February 2025, the UK government borrowed £10.7 billion, far more than the £6.6 billion the OBR predicted as the February 2025 borrowing number back in October. And while borrowing was £10.7 billion last month, the government spent no less than £7.4 of that extra borrowing on debt interest on existing debts. The UK’s national accounts are – and it pains me to write this – beginning to resemble a Ponzi scheme.

This is a situation that has emerged over a number of years. Again, as I made clear at the start of this post, Labour inherited a tricky fiscal position, with the UK already stuck in a high-tax-high-debt doom loop, not least due to the massive policy errors made during lockdown.

But Reeves then severely compounded that mistake with her ideologically-driven Budget last October, yanking up taxation and borrowing sharply, severely damaging business and consumer sentiment and causing growth to stall.

With the fiscal year about to end, the OBR now forecasts that the UK will spend no less than £105 billion on debt interest during 2024/25 – which, as Reeves said, is “more than the government spends on Defence, the Home Office and Justice combined”. She could also have pointed out that the UK government’s debt interest bill this year is almost twice as much as the state spends on schools.

Fast build-up of sovereign debt, rather than long-standing debt levels, really spooks financial markets … the UK’s national accounts are starting to resemble a Ponzi scheme

So our political elite, cheered on by much of the media class – which expresses utter outrage at merely the mention of public spending controls of a barely significant magnitude – is now spending more on debt interest, the financing of the UK’s inability to live within its means, than it is on educating the next generation. And it’s the next generation, of course, that will be picking up the bill.

Far from coming down, Britain’s sovereign debt interest bill is set to soar even higher over the coming years, as we learned in Wednesday’s Spring Statement, reaching “£131.6 billion by 2029/30 as the stock of debt rises”, according to the OBR.

This isn’t only because this Labour government, for all the talk of “security” and “stability”, is planning to borrow even more. It’s also because the OBR now rightly observes that, since the October Budget and the resulting slowdown in UK growth, financial markets are now likely to charge the UK government higher rates of interest to borrow – and for longer.

This can be seen from Graph 6 from the OBR below, showing an upward and significantly higher forecast trajectory of the 10-year gilt yield over the coming five years, compared to OBR projections made back in October.

GRAPH 6: 10-year gilt yields (quarterly averages)

Over recent months, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee has been lowering “base interest rates” – from 5.25pc to 5pc last August, then 4.75pc in November and 4.5pc in February. And it is widely assumed by UK policymakers and commentator that that such cuts to the Bank’s benchmark rate will continue, leading to a related drop in borrowing costs for firms and households.

Financial markets, though, appear to have different ideas – given the rising trend in the borrowing costs large global investors are charging the UK government. And those rising gilt yields themselves have ripple “benchmark” effects, pushing up the cost of credit across the broader economy.

In general, when central banks are taking interest rates in one direction, but bond traders are taking them in another, it is a sign that market expectations are becoming “unanchored” from monetary developments, with policymakers (quite literally) “behind the curve”.

More generally, it points to distress across financial markets, an indication that traders are pricing in higher inflation, a sign of looming trouble. In the end, as history shows, when financial markets are of one opinion and central bank bureaucrats are of another, the central bankers always lose. I am amazed there is not more comment about this now clear breach in the relationship between Bank of England base rates and gilt yields, with these two key metrics having now moved decisively in opposite directions for more than six months.

4) The state is getting bigger – and that poses serious dangers

My fourth observation relating to this Spring Statement is that the UK government spending continues to rise sharply – as was made clear in the OBR technical documents – and the rapid increase in the the size of the state, involving eye-watering increases in taxation and government borrowing, poses grave systemic dangers that risk sparking a serious financial crisis.

The UK’s tax burden – revenue as a share of GDP – is now predicted to rise from 35.3pc this year to a historic high of 37.7 per cent in 2027-28, remaining at a high level until the end of this decade.

“The sharp predicted increase [in the tax burden] in 2025-26 is largely due to the Autumn 2024 Budget increase in employer NICs, which takes effect in April 2025,” says the OBR. “The further forecast rise in the tax take to 2027-28 is mainly due to growth in nominal earnings combined with frozen tax thresholds”, the OBR concludes. The freezing of income tax thresholds from 2021 until 2028, dragging ever more workers into higher tax brackets, was of course implemented by the Conservatives.

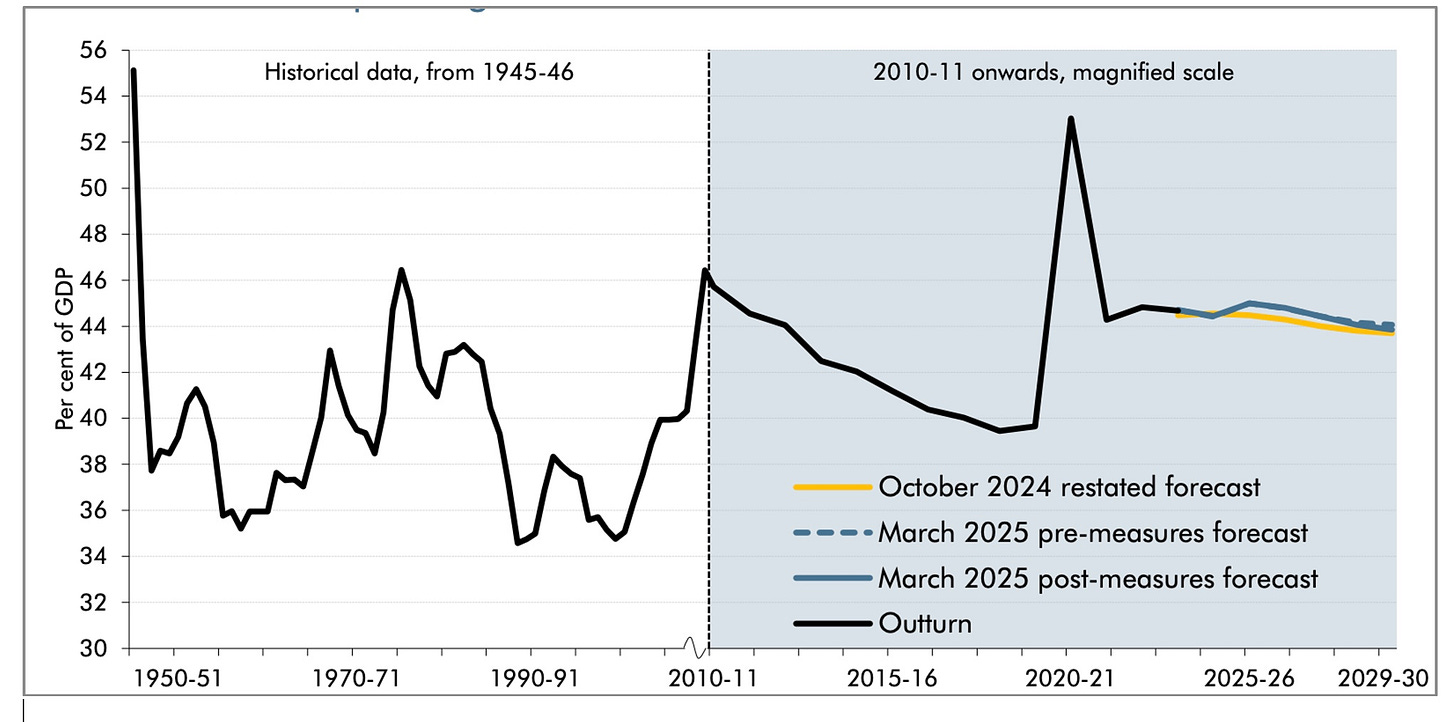

The tax burden is rising, of course, because government spending is also historically high – and that needs to be paid for by both taxation and borrowing. When the Tories took office in 2010, UK government spending was 46pc of GDP, as shown in Graph 7 below. That’s significantly above the 40pc long-term historic average, not least due to the huge damage done to the economy during the 2008/09 global financial crisis – and the resulting surge in both benefit and bank bail-out spending. By 2019, though, after a decade of Tory-led rule, spending was back down to 40pc once more.

GRAPH 7: Public spending as a share of GDP

During lockdown, though, state spending ballooned to a peacetime high of no less than 55pc of GDP and, since then, it’s returned to around 45pc – in part as a result of the economy being released from Covid-era restrictions in late 2021, which automatically lowered the ratio of the national debt to GDP as the economy bounced back. But that spending/GDP ratio has since remained way above the long-term 40pc average and has since started creeping up even more – not least since Reeves’s extremely statist Budget last October.

The OBR forecasts that public spending will fall from 45pc of GDP to 43.9pc by 2029-30. But that relies on growth forecasts during the later part of this decade which may turn out to be over-optimistic (see more on that below). If that growth doesn’t materialise, the spending/GDP ratio would of course then be higher than expected.

Whatever the precise outcome, the reality is that public spending is to remain at historically elevated levels throughout the rest of this Parliament (way above 40pc of GDP) with taxation remaining significantly below 40pc of GDP, while also historically high. This points to ongoing annual fiscal deficits, and therefore annual additional borrowing, of 3-5pc of GDP over the next few years – which is worrying, given that government borrowing costs are already high and are set to rise even more.

The rapid increase in the size of the state poses grave systemic dangers that risk sparking a serious financial crisis.

It strikes me that we simply must find ways to tackle and surmount the UK’s bloated state and the related damaging and horrendously expensive national debt mountain – not least by engendering growth, spreading the state’s liabilities across a bigger overall GDP, to make them much easier to manage.

Unless we do this, we are not only locking ourselves into on-going sky-high debt interest payments. The increase in gilt yields since October means that debt interest payments by the government will hit no less than 8.2pc of total public spending in the current fiscal year, equivalent to 3.7pc of total national income – way, way more than the UK spends on defence.

Debt interest payments at this level are also extremely dangerous, given that they could provide a “gilts strike” – where investors refuse to buy more government debt or will only do so at utterly ruinous interest levels. This is what happened in 1976 – when Jim Callaghan’s Labour government was forced to go “cap in hand” to the International Monetary Fund for a bailout.

I’m not saying the UK will be in such a calamitous position over the coming months or years. But I am saying that the pattern of spending and borrowing, together with the market reaction in the context or rising geopolitical dangers, means it is eminently possible.

It would, in fact, be utterly reckless for ministers not to consider – and take extremely seriously – the reality that such a disastrous outcome, which would cause a currency collapse, inflation spike and severe drop in living standards, could indeed happen.

And with borrowing costs at a 16-year high and rising, but on a far, far larger debt stock than in the aftermath of the 2008/09 global financial crisis (less than 50pc of GDP compared to 100pc now), the chances of a disastrous debt shock are increasing all the time.

Spring Statement Observations 5) – 8) to be published on Sunday 30th March

Growth is the answer, but Labour is hammering growth

The OBR has “bailed-out” Reeves with risky future growth forecasts

“Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long-run it is almost everything”

There is no genuine “fiscal headroom” – so Reeves will soon hike taxes even more.

If only Liam were Chancellor of the Exchequer, we wouldn’t be in this mess, though even better if he’d been chancellor instead of Jeremy Hunt! His solution, like that of Patrick Minford and the hapless, Liz Truss - if she’d been allowed to do as she wanted - perhaps a bit more slowly, is GROWTH, which Rachel Reeves mentions endlessly and clearly knows how to spell without any idea how to achieve it!

Great summary, Liam. Reeves, and much of the elite political/media class, is fiddling while Rome burns.