Firstly, an apology to “When The Facts Change” subscribers for being out of touch. I have been writing a lot in the Telegraph lately – and have also been recording my weekly Planet Normal podcast with my friend and fellow columnist Allison Pearson.

But I need to post more regularly on Substack – and will do so. I will also soon be adding more audio/visual content, not least as I’m building a small studio in my home. Please bear with me as I get “When The Facts Change” properly up and running.

The clip above shows my contribution to a discussion earlier this week on GB News – the bulk of which relates to the subject of this post, namely the latest UK government borrowing numbers, which are actually rather shocking.

I’d recommend that you watch the clip – and if you want more detail on the arguments that I make in the GB News studio, then do please read on.

Fantasy Economics

Inside the UK’s Labour government, there’s a fierce behind-the-scenes battle going on over Rachel Reeves’s next Budget, scheduled for late-October/early November. But the heated discussions within government are shockingly detached from economic reality.

There’s practically no recognition among cabinet ministers, and certainly not Labour’s backbench MPs, that the British state is, quite literally, teetering on the edge of bankruptcy.

There’s little acknowledgement that the sharp tax rises announced in Reeves’s last Budget in October 2024 have stalled the economy – GDP has been contracting, shrinking in both April and May – or that rising tax rates are now leading to falls in total tax revenues.

And there’s certainly no appetite at all within the Labour party for the controls on spending needed to avert a major fiscal crisis – as recent government U-turns on welfare reform have shown.

Labour’s £40bn of tax rises last year took the UK’s tax burden to its highest level since the early 1960s. But during the twelve months to this April, the fiscal year 2024/25, government borrowing still surged to £148bn instead of the £87bn originally forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

And this week we learned that the government borrowed no less than £20.7bn in June alone, some £6.6bn more than the same month last year. This is the second-highest June borrowing figure on record, outstripped only in June 2020 at the height of the Covid lockdown, when the entire economy was shuttered and the state was spending mightily on furlough and other support measures.

The stark reality is that the UK government is now borrowing not so much to spend more on the NHS or other public services, but largely to pay the interest on its ballooning national debt – as this post will demonstrate. Meanwhile, the economic growth that would deliver more tax revenues and stabilise our public finances is now being crushed, as companies and households grapple with higher tax rates and hunker down, curtailing spending and investment, ahead of widely-expected further tax rises in Reeves’s upcoming Autumn Budget.

UK politicians continue to operate in a world of fantasy economics, as does almost our entire media class, demanding ever higher spending, ignoring the soaring national debt and spiralling debt-interest payments and refusing the most modest spending controls. Witness the government’s inability to even moderately rein-in the forecasted surge in benefit spending over the lifetime of this Parliament.

Meanwhile, the Treasury/No.10, having ruled out tax hikes for “working people”, is now floating further taxes on businesses and savings that risk entrenching economic stagnation – and undermine our public finances even more.

The UK government is now borrowing not so much to spend more on the NHS or other public services but largely to pay the interest on ballooning national debt

It is absolutely the case that, after years of political and managerial drift, the Conservatives left Labour a difficult fiscal inheritance – with taxation already sky-high and national debt at around 95pc of GDP. Whenever I write or speak publicly about the UK’s public finances, I acknowledge that reality – as I did in the clip above.

But the fiscal dangers Britain faces have been very significantly heightened by Labour’s policies since the party came to power in July 2024, as spending, borrowing and tax rates have been pushed up even more – and the warnings I’ve been issuing for many months, about rising government borrowing costs and spiralling debt-interest payments are now being echoed from quarters that are difficult to ignore.

Last week, for instance, the OBR itself issued an unprecedented, damning assessment of how badly public spending is out of control, remarking that the UK’s fiscal position is “vulnerable” and “facing mounting risks”, the challenges “daunting”.

And Paul Johnson, bowing out as director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, is now lambasting MPs of all parties for “living in a dream world”. Johnson said he was “in tears” at the “fantastical economic beliefs that seem to be assailing ever more people among our political class and beyond.” There is, he wrote, “not a hint of seriousness to be found” ahead of the forthcoming Budget.

That is indeed the reality – there are very few in our political and media class willing to confront reality and get beyond “fantasy economics”.

Displacement Activity

In April 2024, the OBR forecast the government would borrow £87bn over the subsequent twelve months. When that financial year ended in April 2025, the figure was £148bn, as mentioned above, an astonishing 70pc more. Endless political and media discussions about whether ‘fiscal headroom’ is £5bn or £10bn in five years’ time – the definition of Reeves’s ‘fiscal rules’ – are utter displacement activity. We can’t even get within £60bn of our borrowing estimate within the current financial year.

The graph below highlights just how dramatically official OBR forecasts of government borrowing in 2024/25 escalated as the year progressed – a reality ignored as politicians and the media continue to play parlour games over the prospect of “£10bn of headroom” in 2029/30, the scheduled end of the current Parliament. This is fantasy economics in action.

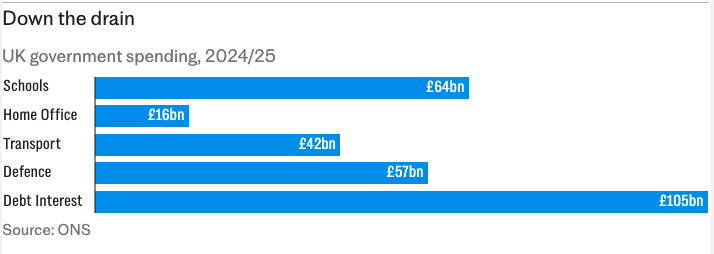

The UK government spent no less than £105bn on debt interest during the last fiscal year – almost twice the annual defence budget, far more than we spend on schools. So no less than 70pc of what the government borrowed in 2024/25 (£105bn out of £148bn) was spent not on public services or benefits for the needy, but on servicing our ever-growing pile of national debt.

And we learned earlier this week that of the £20.7bn borrowed during June, a staggering £16.4bn of that borrowed money, over 80pc, went on debt interest. The UK’s public finances now resemble a “Ponzi scheme”.

When four-fifths of the money you’re borrowing is being used to pay the interest on your existing and ever-growing pile of debt – using a new credit card to pay merely the interest bill on all your other credit cards, not tackle the debt itself – then you are obviously in serious financial distress.

Over 80pc of government borrowing in June was spent on debt interest

A major and almost entirely unacknowledged reason why our debt interest bill is spiralling out of control is because Britain has by far the highest share among advanced economies of “index-linked” government debt – with interest payments that rise with inflation. Some 30pc of our outstanding state debt is tied to inflation, compared to just 5pc in the US, Germany and France and 12pc in Italy (the G7’s second highest). And the recent sharp rise in UK inflation is ratcheting up government debt interest payments even more.

Much of the commentariat thinks that, if Reeves repeats what she did in last October’s Budget, sharply increasing tax rates this autumn too, she can plug the gap, reduce borrowing and avoid a sovereign bond market melt-down. That is NOT the case.

Because Reeves’s tax rises so far, not least her massive £25bn annual hike in employers’ national insurance contributions (NICs), have crushed hiring and investment, along with broader economic growth, weakening tax revenues and further undermining our public finances.

Stung by recent massive forecasting errors during 2024/25, the OBR – full of public-sector economists who are broadly sympathetic to Labour – is now starting to issue stark warnings about the limits of UK taxation.

Reeves’s higher tax rates have been hammering economic activity, undermining growth and weakening our public finances even more

“The ratio of tax to GDP is now at levels we haven’t seen since the Second World War…the scope to simply just raise more and more tax revenue is definitely limited”, said David Miles earlier this month. Miles is extremely senior, one of only three members of the OBR’s Budget Responsibility Committee. “With any further hikes creating so many disincentives around saving, investing and working”, Miles continued, looking for tax increases “wherever you could find them” will cause “serious damage to the growth potential of the economy”.

And when the economy is stalled by high tax rates, as it now is, government benefit spending is higher and tax revenues are much lower, making the gap in the budget even wider…

Long Hot Summer

The UK’s consumer price index (CPI) was 3.6pc higher in June than the same month in 2024 – well above expectations and significantly higher than the Bank of England’s 2pc inflation target. The broader retail price index (RPI) rose even more, by 4.4pc. Unemployment is also up, hitting 4.7pc during the three months to May, a four-year high. And, as I mentioned above, GDP contracted in both April and May, by 0.3pc and 0.1pc respectively.

It’s now screamingly obvious Labour’s “pump priming” of the economy, trying to generate growth by upping state borrowing and spending, isn’t working. Worse than that, the government’s crude Keynesianism is now pushing Britain towards a budgetary crisis every bit as serious as during 1976, when the UK was bailed-out by the International Monetary Fund – a catastrophe that seems to have been aired-brushed out of our political and media consciousness.

Reeves’s higher tax rates have been hammering economic activity, causing tax revenues to fall. Yet Labour’s leadership, driven by ideological fervour and fearing the party’s increasingly strident far left, keeps pushing spending up regardless.

It’s now screamingly obvious Labour’s “pump priming” of the economy, trying to generate growth by upping state borrowing and spending, isn’t working

The sharp rise in the rate of NICs, for instance, has caused hiring to plunge since it was announced in last October’s budget, undermining NIC revenues overall. Labour’s higher capital gains tax rates, introduced in October, mean investors aren’t selling assets, causing CGT revenues to plunge. Higher stamp duty is caused the housing market to seize up – there were just 81,000 transactions of residential properties in May, a huge decrease from 177,000 in March, as the impact of stamp duty changes kicked in.

A more punitive non-domicile tax regime and much higher inheritance tax on businesses has also sparked an exodus of wealthy individuals, with countless UK entrepreneurs moving abroad. The top 1pc of earners generate almost 30pc of all income tax receipts, with the top 5pc paying around half. But when you push the seriously rich overseas with a student-politics tax regime, they will often stop investing and close their UK-based businesses too. So the revenue loss goes way beyond income tax, spreading across the gamut of employment and corporate taxes.

As a former asset manager, I talk to senior people at the global pension funds, insurance companies and other institutional investors that lend governments serious money. So when I say that the financiers upon whom the UK depends to lend money to our government are not only deeply unimpressed but seriously alarmed and increasingly nervous about this Labour government’s actions, that’s direct from the horse’s mouth.

It’s anyway clear investors are demanding ever higher returns to bankroll this increasingly spendthrift government. The interest rates our government pays to borrow are now at their highest level since 1998, but on a far greater volume of debt – approaching 100pc of GDP, rather than 35pc of GDP back in the late 1990s.

The UK’s benchmark 30-year gilt yield has lately breached 5.5pc – having been way above 5pc for the whole of this year. Borrowing costs have for many months now been consistently much higher than the 4.85pc peak they momentarily touched during Liz Truss’s “mini-budget” crisis in October 2022. Yet the media’s reaction, hysterical back then, is now for the most part ridiculously complacent.

Last August, just after Labour took office, the 30-year yield was below 4.5pc. Since then, increasingly sceptical investors have pushed it a full percentage point higher. During this same period, the Bank of England has cut its benchmark borrowing cost from 5.25pc to 4.25pc, a percentage point in the opposite direction. “Market rates” and “policy rates” moving against each other are a clear sign of brewing systemic danger. The warning signals are flashing red, yet no-one in a government addicted to spending wants to acknowledge what’s going on.

Outlier Nation

“Borrowing costs are going up around the world”, bleat fresh-faced government spin doctors. Rachel Reeves herself made the same argument, when appearing earlier this week before the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee.

While that’s true, UK gilt yields and total debt service payments are now easily the highest in the G7. As of the time of writing, the UK 30-year sovereign yield is 5.46pc, significantly higher than the US (4.94pc), France (4.17pc) and Germany (3.21pc). Even the governments of previous “debt-crisis” nations can now borrow a lot more cheaply than the UK – namely Italy (4.46pc), Greece (4.25pc) and Spain (4.12).

What really worries serious bond traders is the UK’s stark outlier status when it comes to the share of “index-linked” state debt, as mentioned above. Not only is almost a third of our outstanding sovereign debt tied to inflation, five- to six-times more than almost all comparable nations, it is linked to inflation as measured by the RPI (which rose 4.4pc last month, far more than the headline CPI number).

Reeves continues to claim that the government has no issues getting global investors to lend it money. Yet even though the gilt yields we are paying are already comparable high, the true price we are paying to service our debt is actually far higher, given that in a bid to keep headline borrowing down, we have been offering lenders a taxpayer-backed inflation hedge by issuing “linker” bonds to a far, greater extent than any other major economy.

What really worries serious bond traders is the UK’s share of “index-linked” state debt - which is five-to-six times higher than comparable nations

Again, approaching a third of the UK government’s outstanding government debt is now RPI-index-linked, compared to around 5pc in the US and Germany and 10-12pc in France and Italy. This surge in index-linked debt issuance reflects, in part, an attempt by the authorities to assuage long-standing concerns among bond investors about the UK’s vast government off-balance-sheet liabilities. Yet our headline gilt yields are anyway still the highest in the G7, despite so much of our debt being index-linked.

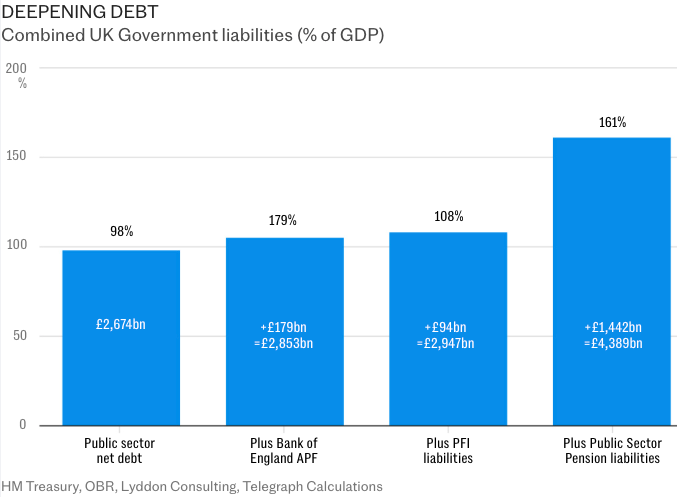

The UKs’ off-balance sheet public sector liabilities include debt accrued under the Bank of England’s alarmingly opaque “asset purchase facility” (APF), the disastrous “private finance initiative” (PFI) but, above all, the on-going trillion-pound-plus bill for still insanely generous pensions for state employees.

These gargantuan statistical wheezes means the UK government’s actual liabilities are way higher than the headline national debt figure – around 160pc of GDP if you use very conservative estimates of the cost of public sector pensions, as I have in the graph above. Such stark realities, again, are entirely absent from practically any public discussion of Britain’s public finances. But serious financial analysts, and the bond investors they advise, are all to aware of the genuine position of the UK’s national balance sheet.

As well as the UK’s “outlier” status when it comes to index-linked debt, much of the private money invested in UK gilts is “levered” – or also borrowed. And when the backers of the government’s backers get worried, as I know they now are, they will eventually “margin call” creditors, igniting a sudden and self-reinforcing sell-off that sends yields and economy-wide borrowing costs into orbit.

Looming in the background, then, as politician and journalists indulge in meaningless “faux-clever” discussions about whether “fiscal headroom” is £5bn or £10bn in 2029/30, is the spectre of 1976. Back then – again under a big-spending Labour government, in hoc to public sector unions and belligerent backbenchers, which kept pushing tax rates up – the UK ended up going “cap-in- hand” to the International Monetary Fund for a bail-out, an episode which sparked a plunging currency, sky-high inflation, and years of economic and political chaos.

Britain is now hovering close to the cliff-edge of a similar fully-blown sovereign-debt crisis. Back in 2008, in the aftermath of worst financial collapse since the late 1920s, HM The Queen asked, “why no-one saw this coming?”. The same can’t be said this time around – lots of serious people, not least highly-influential investors, are now seriously concerned that the UK’s public finances are on the brink of systemic collapse.

Yet almost our entire political and media class – not least our Labour government – remains determined to ignore this reality.

Share this post