Ahead of Rachel Reeves's Spending Review – Who Will Stand Up for Reality?

The most ideologically left-wing UK government since the 70s is making ever higher borrowing and spending commitments, cheered on by a media class that, for the most part, is economically illiterate.

Ahead of Rachel Reeves’s Spending Statement on Wednesday 11th June, I’ve been doing a fair amount of punditry relating to the UK’s public finances. Recent outings have included The Spiked Podcast, The Current Thing with

and the chat posted above with Nick Ferrari on LBC Radio – in which, despite the dire state of our national accounts, Nick and I managed to have a laugh along the way.Before the Statement itself, I thought I would put together a round-up for When The Facts Change readers on the state of the public finances.

This Isn’t 1997 …

The first thing to say is that this isn’t 1997 and today’s Prime Minister Keir Starmer is most definitely not Tony Blair. The original “New Labour” leader enjoyed a “golden inheritance” after he entered Downing Street – the national debt was equivalent to just 36pc of GDP and the UK economy grew by 3-4pc per annum over subsequent years.

This buoyant growth kept lots of tax revenue rolling in and the welfare and broader benefit bill mostly under control, so the public finances remained in reasonable shape. This was despite the big-government instincts of Blair’s high-spending Chancellor Gordon Brown.

During New Labour’s early years in government, Brown for the most part kept his statist instincts in check – as his party tried to reassure the mainstream voters who had put Blair in office that Labour could indeed be trusted not to destroy the public finances. Back then, after all, memories of the 1976 IMF crisis – when the UK had suffered the ignominy of being bailed out by the International Monetary Fund under Labour’s Jim Callaghan - loomed large.

After a few years of discipline, though, once those ghosts of the 1970s were seemingly banished, Brown let his “Iron Chancellor” mask slip and let rip, trying to upstage Blair by spending his way to a popularity with the public that he would never achieve. But because the economy, for the most part, kept growing at a reasonable pace, the public finances remained broadly stable – until they were totally upended by the global financial crisis in 2008. That was the result not so much of fiscal profligacy, but deeply inadequate financial regulation, the result of vigorous lobbying on both sides of the Atlantic, and white-collar criminality across Wall Street, the City and elsewhere.

Today, in stark contrast to 1997, the national debt isn’t 36pc of GDP but almost 100pc – and the UK economy, instead of the relatively buoyant growth of the pre-financial crisis era, is locked in a high-government-borrowing-and-spending, high-tax, low-growth doom loop. This was a predicament presented to Labour after fourteen years of Conservative-lead rule – in no small part due to the huge economic damage caused by Covid-related lockdown. But it was a bad situation which Starmer’s government has since made considerable worse.

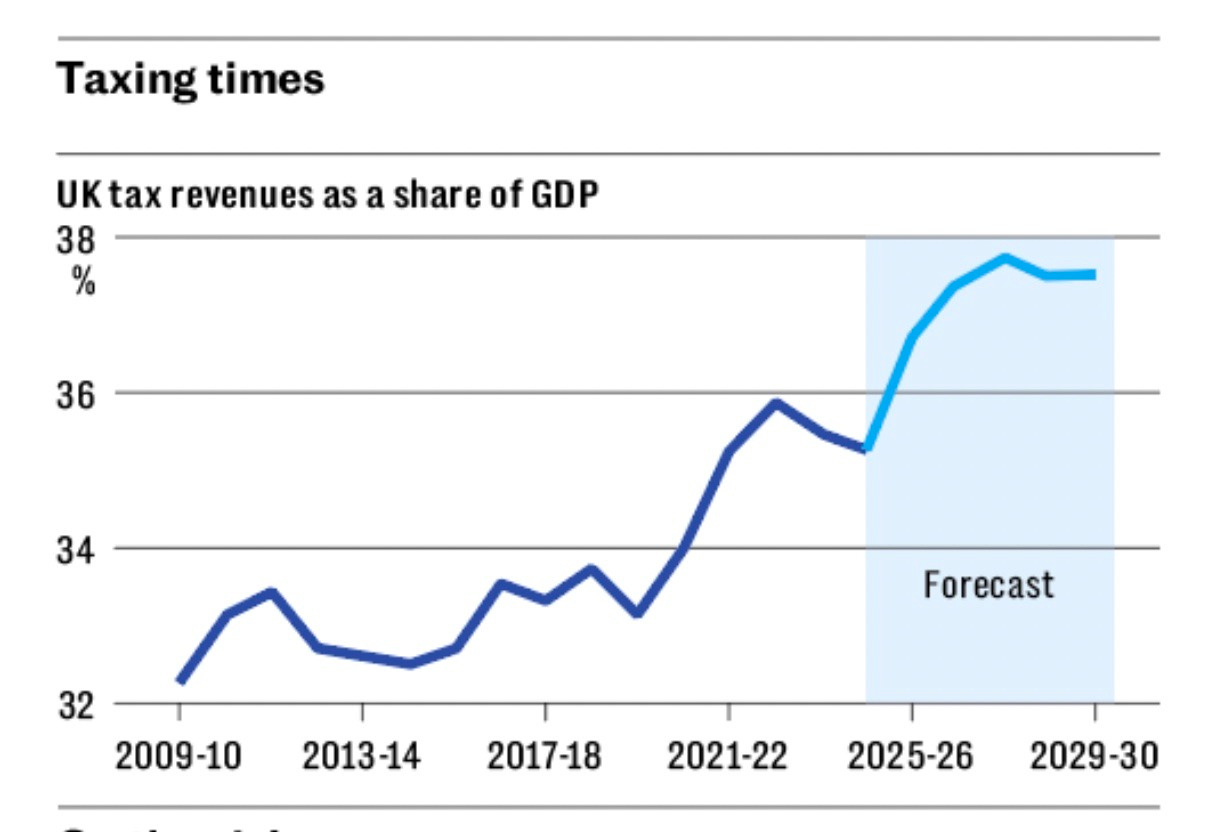

Tax revenues as a share of GDP – the “tax burden” – is currently approaching 38pc of GDP, a 70-year high. The scale of our debts means the UK government now spends s jaw-dropping £105bn per year in debt interest – twice what we spend on defence, more than schools and transport combined. Financial markets have become increasingly nervous about the weakness of the UK’s public finances over recent months, so have been demanding higher interest rates to lend to government, pushing up borrowing costs across the broader economy, despite the Bank of England lowering “base” interest rates – as I’ll explain below.

And yet all the signs are that Labour is about to spend way beyond the country’s means once again in Rachel Reeves’s Spending Review on Wednesday – resulting in even higher borrowing and a heavier tax burden down the line, further increasing the already looming danger of another 1976-style fiscally-driven financial crisis.

“We can’t tax and spend our way to higher living standards and better public services,” said Reeves during her Spring Statement in March. I’m not sure the Chancellor ever believed this – or if she did, her senior colleagues don’t agree.

Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner, in a deftly leaked memo, has recently floated yet more tax rises on firms, property and pensioners – measures that she claims would raise another £4bn a year. Keir Starmer, equally desperate to appeal to left-wing Labour activists, lest the “Red Queen” outflanks him, has lately made his own new spending pledges – diluting already pretty unambitious cost control measures his own government only recently announced.

The Prime Minister made clear he wanted to restore broader access to winter fuel payments while scrapping Labour’s policy of maintaining the two-child cap on child benefit – at a combined cost of least £5bn per annum. And now he has effectively pushed Reeves into committing to those extra expenditures – commitments she clearly felt politically obliged to meet, lest she loses her place in the Labour party’s pecking order, or her job as Chancellor entirely.

So this isn’t 1997, and Starmer isn’t Blair. Today’s Prime Minister, and pretty much the entire government front-bench, is way to the left of its New Labour equivalent of almost 30 years ago (most of whom I knew, by the way, as I was in those days a Westminster-based Political Reporter for the Financial Times).

I should also add that, back then, Blair and his team made sure there were always people in and around Downing Street, when the big tax and spending decisions were made, with a deep, professional understanding of the realities of financial markets. Two that spring to mind are former Goldman Sachs partner Gavyn Davies and the late Derek Scott, who also had extensive City experience.

There is currently no-one in and around Starmer’s top team with a serious understanding of financial markets – and a sophisticated grasp of how the major institutional investors who buy and sell government debt may behave under various scenarios.

This is the most ideologically left-wing British government since the 1970s, the senior members of which are now goading each other into ever higher borrowing and spending commitments – in the face of increasing scepticism among the kind of leading global investors who bankroll the government, scepticism the Prime Minister’s inner circle, the entire Labour party in fact, seems utterly determined to ignore.

And this incredibly risky process is being cheered on by a UK media commentariat that is, with very few exceptions, unquestioningly supportive of ever-higher government spending and borrowing under all circumstances – in other words, economically illiterate.

Ahead of Reeves’s Spending Review, that is where we are at.

An Economy Stuck in Second Gear

As soon as Labour won the general election in July 2024, senior parties figures began to claim they had “discovered a £22bn Tory black hole on entering office”, using that narrative to try to justify tax rises not in the party’s election manifesto. The reality is that the need to consolidate the public finances and the upcoming shortfall in government revenue was, ahead of last July’s election, “obvious to anyone who dared look”. Those are the words of Paul Johnson, Director of the Institute of Fiscal Studies – no friend of the Tories and among the UK’s most widely-respected fiscal economists.

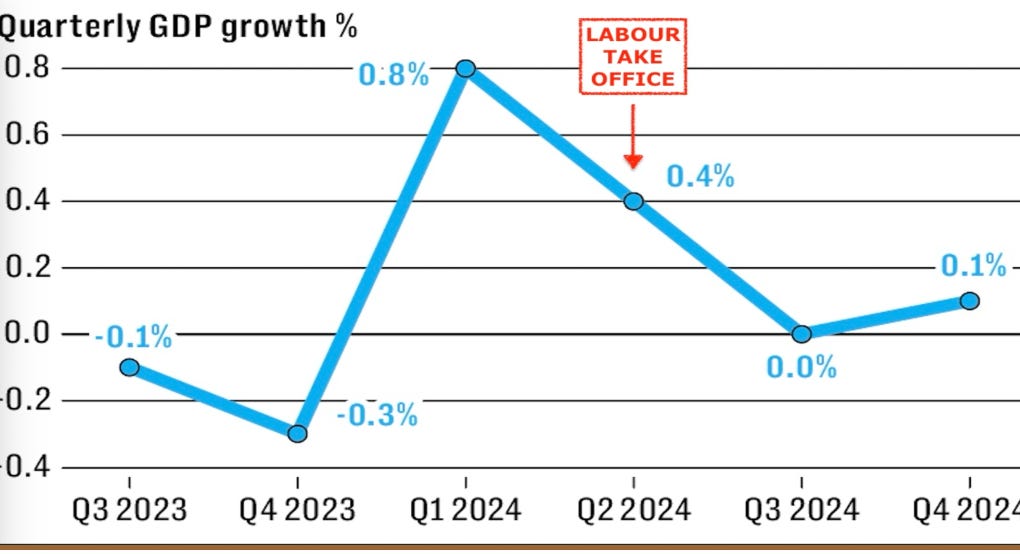

Labour’s gloomy rhetoric, combined with £40bn of tax rises and £30bn of extra borrowing announced in Reeves’s October 2024 budget, hit consumer and business sentiment badly during the second half of last year. Growth stalled, with the economy barely expanding during Q3 and Q4 2024 – which undermined tax revenues and pushed up welfare spending, weakening the public finances even more

Since last autumn, the Bank of England and Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) have both downgraded the UK’s 2025 GDP growth forecast – from 1.5pc to 0.75pc and 2pc to 1pc respectively. Yes, preliminary data suggests the economy grew by 0.7pc during the first three months of this year - Q1 2025. But that was largely due to the temporary “sugar rush” of bumper public sector pay rises (paid for by Labour with borrowed money) and a 3.8pc surge in exports, as firms tried to preempt Donald Trump’s tariffs ahead of their eventual introduction in April. This one-off export surge was significant – it followed three successive quarterly declines in UK exports, and added no less than 0.4 percentage points to GDP growth.

In April 2025, the UK’s Composite PMI index, a survey of business leaders’ views and activities, fell to 48.5 – with readings below 50 pointing to economic contraction. This was the first sub-50 reading since October 2023 , with sector PMIs for both manufacturing (45.4) and services (49.0) pointing to falling economic output.

The S&P Global UK Composite PMI for last month, May 2025, rose to 50.3 – marking a return to marginal growth in private sector activity after April’s contraction. Yet this reading, while indicating a slight rebound, is still the second-lowest since October 2023. The improved composite number was also driven entirely by services, masking a still struggling manufacturing sector, which recorded a PMI in May of just 46.4, while showing the sharpest drop in new orders in 19 months.

UK inflation remains high, with the consumer price index rising 3.5pc during the year to April, up from 2.6pc in March. Food is 30pc more expensive than prior to lockdown and household energy prices 60pc higher – with real wages yet to catch up. The cost-of-living crisis is by no means over for hard-pressed UK households.

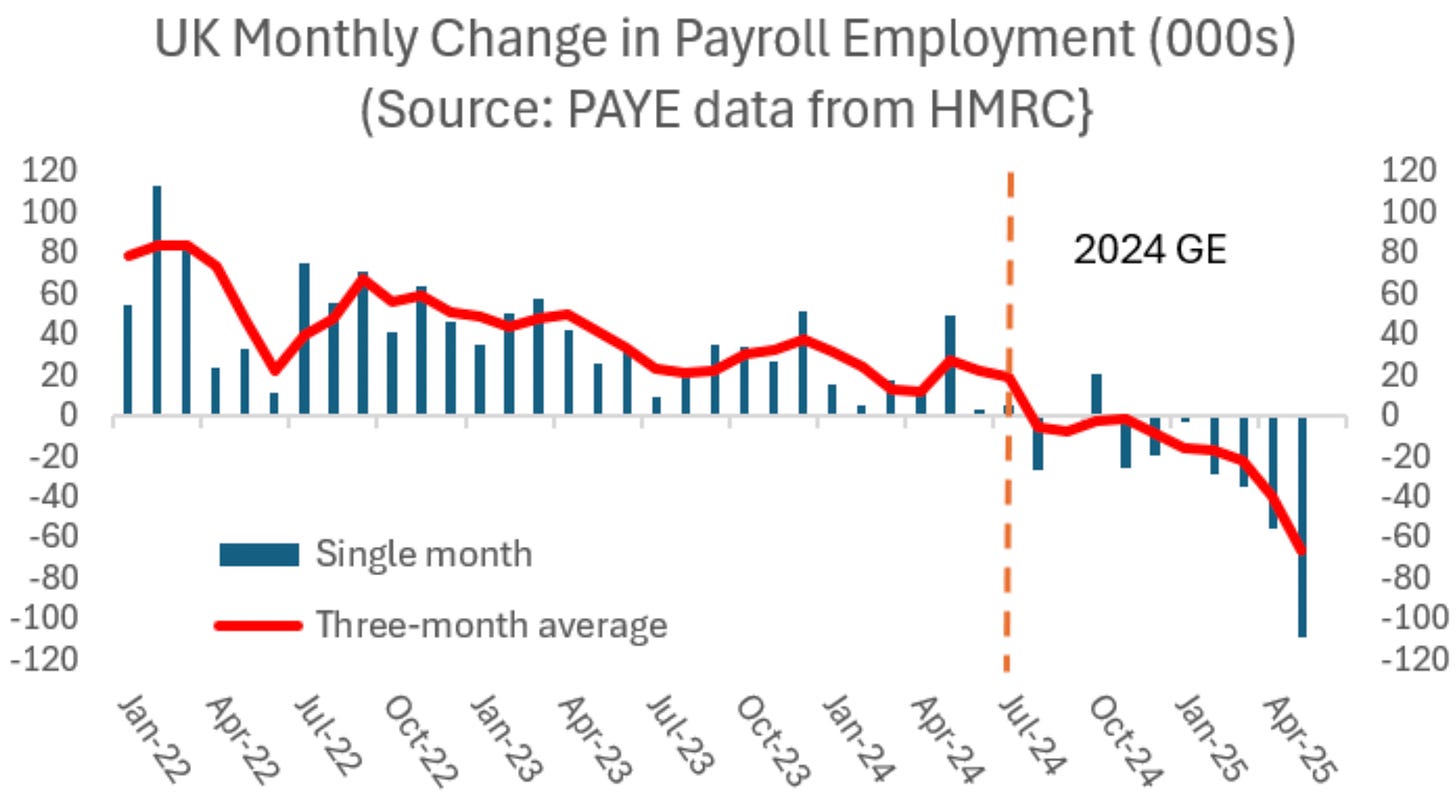

Yet, supply-chain cost pressures remain significant, which will push CPI inflation up even more during the second half of this year – as UK firms deal with rising wages, ever rising utility bills and higher taxation. Labour’s £25bn annual rise in employer national insurance contributions and inflation-busting minimum wage increase, both announced last October but introduced in April, means hiring is now at its slowest since Covid lockdown, with tax uncertainty hitting investment also – both of which are seriously undermining growth.

Provisional data just released show payroll employment fell by a vast 109,000 in May alone – hardly surprising given how much more expensive Labour has made it to employ people. As this graph shows, employment has fallen almost every single month since Labour took office in July 2024. UK firms are now shedding jobs at the fastest pace in five years. And that’s before Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner introduces her new trade-union-driven Employment Act, currently going through Parliament and set to make it even more expensive and difficult for firms to hire new workers.

Ideology Above Reason

Since July 2024, this government has consistently demonstrated a depressing and worrying tendency to prioritise ideology above reason. Reeves raised the top rate of capital gains tax by 4 percentage points in her budget last October, while stripping back reliefs offered to those selling companies or shares that will, on official estimates, blow a £23bn hole in the public purse – but she is pressing ahead anyway. Labour’s spiteful inheritance tax assault on farmers risks a food crisis and will also cost the Treasury £2bn. The government’s vindictive attack on private schools is already proving to be a bad idea, and its talk of taxing the wealthy has triggered an exodus of millionaires whose taxes we desperately need.

Yet, while the OBR has very publicly downgraded its growth forecasts for 2025, the spending watchdog – itself a hotbed of big-state thinking by taxpayer-funded analysts with scant experience in the real world – has significantly upgraded all future GDP forecasts, in a bid to make the sums add up. The increase in the dark blue bars from 2026 onwards in the chart below is based on assumed increases in investment and productivity improvements which, on current form, look highly unlikely to materialise. As Labour keeps raising taxes, and throwing ever more regulation and red-tape at the UK’s increasingly beleaguered employers, these rosy assumptions about future GDP growth – upon which the UK’s entire fiscal outlook is constructed –look increasingly unrealistic.

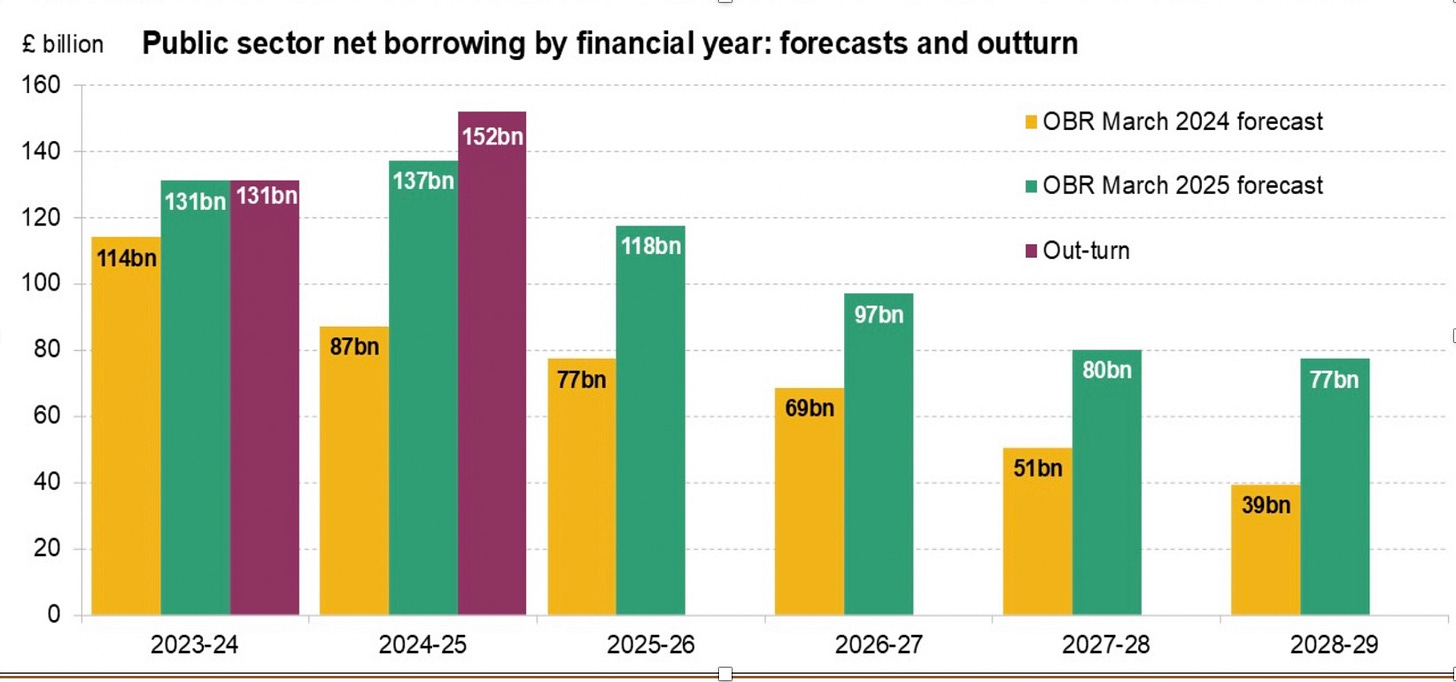

The reality is that UK government spending has long been running well ahead of economy’s ability to generate tax revenues, with annual deficits adding to the national debt each year. The last time we ran an annual budget surplus was 2000/01, almost a quarter of a century ago. Each year, the OBR pretends that borrowing will be much lower than it actually will be in future years – the pattern in 2023-24 and 2024-25 shown in the graph below is long-standing and set to extend into the future. And each year the media fixates on these forecasts, without ever looking back to see if they actually worked out !

The UK’s “transitory” post-Covid inflation – which some of us warned about – saw CPI growth peak at 11.1pc in the autumn of 2022. That resulted in 14 successive rate rises by the Bank of England – to 5.25pc.

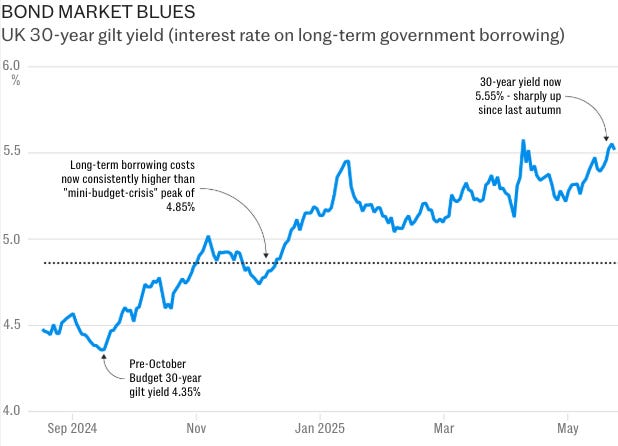

Since August 2024, the base rate has been lowered four times to 4.25pc – amidst widespread predictions rates will fall further. But while the Bank of England has dropped base rates a full percentage point over last nine months – the UK’s 30-year year gilt yield has moved almost the same amount in entirely the opposite direction. This is because for all the rhetoric about “Tory black holes” and “fixing the foundations of our economy”, investors have become increasingly sceptical of Labour’s financial plans – specifically, the impact of higher taxation and spending on GDP growth and the knock-on effect of low growth on the public finances – and have therefore demanded increasing returns to lend to the UK government.

So, since last summer, financial markets have been at loggerheads with policymakers, with gilt yields rising as the Bank of England’s base rate has been sharply falling. This is a sign of looming systemic danger. And, by the way, as the graph show, yields are now consistently above where they were during the Oct 2022 ”mini-budget” crisis. Yet there has been little or no media outcry.

It May Take a “Proper Crisis”

The UK’s debt interest bill is now emerging as a major political issue – with the cost of servicing our burgeoning national debt going up sharply as gilt yields rise, not only because the debt is growing but because market confidence is seeping away.

The government’s £105bn annual debt service bill, much of it paid for with additional borrowing, is vast. By comparison, the state spends £42bn on transport, £57bn on defence and £64bn on schools. This country’s leading broadcasters should be talking about our gargantuan debt interest bill every single day – as I said to LBC’s Nick Ferrari during the exchange at the top of this post.

That may help to start shifting the prevailing media narrative – that more public borrowing and spending is always and everywhere a good thing and that anyone who raises objections is somehow morally suspect.

The reality is that a third of UK state debt is index-linked – and a 1 percentage point yield increase costs £12bn-plus in additional annual debt services charges. The fact that the cost of servicing so much of our state debt rises with inflation makes the UK particularly vulnerable in the so-called “ugly baby” contest, as global investors assess which highly-indebted Western nation looks most financially suspect.

After the £40bn of extra taxation and £30bn of additional borrowing in her “once in a generation” budget last October, Rachel Reeves promised “no more tax rises”. Yet as Labour’s spending commitments keep spiralling, as we’ll no doubt see in this coming Spending Review, the UK’s public finances will continue to deteriorate – as ever-rising taxes curtail job-creation, enterprise and growth, squeezing tax revenues even further.

In my travels, I talk not only to countless politicians and policymakers, but also lots of highly-sophisticated market-focussed invest professionals. They now talk openly of a “gilts strike” or the prospect of very sharp increases in government borrowing costs, amidst a sudden fall in the value of sterling, driven by government profligacy. As these danger swirl, the UK’s political and media class obsesses about political tribalism, and the amount of “fiscal headroom” Reeves may or may not have in 2028/29.

For the record, Reeves left £9.9bn of headroom in her March 2025 budget, on total spending of £1,351bn in four years’ time – a contingency of well below 1pc by the end of this Parliament, so small as to be utterly meaningless. Yet OBR forecasts for the next year, even the next quarter are constantly proved wrong by vast double-digit billion magnitudes – see graphs above.

Arguing obsessively about single-digit billions of difference in deficits in four years’ time – deficits that are themselves the difference between two vast numbers, both of them highly uncertain forecasts – and pretending that amounts to fiscal scrutiny is the ultimate displacement activity. Yet that is the political and media game we play in, around and after every major fiscal statement.

Meanwhile, we ignore the genuine fiscal realities we face today, the realities staring us in the face – debt interest and rising gilt yields, to say nothing of the vast off-balance sheet liabilities which mean our national debt, rather than 100pc of GDP, is actually closer to 200pc.

For now, this is the graph that counts – and, which, if it was brought more prominently to public attention, would lead to demands for our public finances to be managed properly, challenging the “big state, high spending” consensus promoted by the majority of newspapers and practically every mainstream broadcaster.

Yes, I know when you ask voters if they want more public spending, then they say “of course” – almost everyone will say that when asked by a pollster if they want more free stuff. But the majority of people know in their bones that at some point the music will stop and ultimately they want to be led by someone who gets that.

And, of course, the public will be absolutely furious when the music does indeed stop, and there is major turbulence on government bond markets resulting in serious economic and financial fall-out – fall-out during which, of course, it will be the least well-off who suffer the most.

And meanwhile the same politicians and pundits who ignored reality and drove us over the edge will opine: “Why did nobody see this coming”?

While firm fiscal management isn’t politically popular, most voters understand that when it’s needed it’s needed – think back to the late-1970s, after the IMF debacle, or even the early 2010s, following the global financial crisis, times when there was widespread clamour for grown-up financial management to rescue the country from chaos.

All the major parties, mistaking opinion polls for genuine public sentiment, are continuing to loudly champion big spending and yet more borrowing, as they no doubt will during tomorrow’s Spending Review, despite all the now screamingly obvious dangers.

Who will stand up for reality?

That reality is that a situation that is unsustainable will not be sustained. My fear is that we’re now at the point that it may take yet another “proper crisis” to shift the political dial, for that lesson to be learnt once more …

Thank you for putting pen to paper so powerfully. It seems such an existential crisis that, for the good those of us bystanders and the UK in general, your next piece might be to set out your thoughts on a roadmap out of this.

Liam, I completely agree with you but it's worse than that I'm afraid. We have a Labour Front Bench that has never worked in the Private sector filled with:

1. Professional Politicians/SPADs (any number of economically clueless new Labour MPs on BBC2 Politics Live)

2. Trade Unionists (Deputy PM)

3. Quangos / Charities / Pressure Groups (Education Sec/DWP Under Sec)

4. Apparatus of Government including the Treasury (Chancellor/Home Sec)

5. Qualified Lawyers (PM/Chief Sec to Treasury) / unqualified Lawyers (Business Sec)

6. Various other non-business "Klingons"

And they then have the temerity to tell Businesses what is good for them... They are completely hypocritical when it comes to:

i. Public Sector spending (now 45% of GDP) and value for money (Oxymoron)

ii. The civil service workforce (c20% of total) and appalling Public Sector productivity (below 1997 levels) and DB Pensions ratchets leaving future generations "skint": and That's before we get to

iii. Inimical to growth policies (increasing Employers NI)

iv. The fact that 54% of the population take out more in public services than pay in tax and then squeezing those who put in, more and more: and

v. A belief in a Magic Money Tree that doesn't exist. The retreat on Winter Fuel & benefit reform has been abject

This ends two ways:

A. As you say a Fiscal event a la Truss which if we have more "turbulence" could be sooner than we think: or

B. A Thatcher moment where a Leader takes the country in a completely new direction ... Obviously Trump is not the exemplar, but what about Milei in Argentina, is there anything we could learn from them?